The World’s Most Monstrous Plants (Part II)

Emily Ellis

You likely won’t have to stray from your garden this Halloween to find monsters more gruesome, destructive and terrifying than anything conjured up in Hollywood. While many of us pass by the pretty flowers of jimson weed or wolfsbane without a second thought, seemingly innocuous plants like these have been responsible for countless deaths, been at the core of our most chilling tales, and inspired truly reprehensible human actions. The power of plants should not be underestimated - as the list below shows.

Every spooky story deserves a sequel, and to celebrate Halloween this year, here is our second post of the world’s most monstrous plants, several which are growing at Oak Spring. (Click here to read about mandrakes, deadly nightshade, giant hogweed, and other scary flora from 2019’s list of The World’s Most Monstrous Plants.)

Scroll below - if you dare.

Sheep-eating plant (Puya chilensis)

Photo: Mar del Sur

An evergreen perennial native to Chile, this plant isn’t actually carnivorous, but what it does to sheep and other unfortunate woolly animals that stumble into its midst is pretty sinister. While most plants with spines use them for protection, scientists theorize that the sheep-eating plant uses its long, sturdy spikes for hunting: it traps animals with thick fur, which then starve to death and decompose, providing rich, localized food for the plant. The sheep-eating plant made the news in the UK a few years ago for blooming at U.K.’s Royal Horticultural Society at Wisley after 15 years, although that specimen was fed on liquid fertilizer rather than tortured mammals.

Devil’s snare (Datura stramonium)

French School, Collection of botanical studies. c. 1820

With common English names that include devil’s snare, thornapple, hell's bells, devil's trumpet, devil's weed, stinkweed, locoweed, Beelzebub’s twinkie, and devil's cucumber, you know this is one trouble-making plant. Datura stramonium, native to North and Central America and now widespread throughout the world, has been poisoning people and unsuspecting livestock for hundreds of years. All parts of the plant contain high levels of the deliriants atropine, hyoscyamine, and scopolamine - so even if ingesting it doesn’t kill you outright, it will likely take you on one unpleasant trip. In the United States, the plant is often called jimson or Jamestown weed because of a group of hapless soldiers in Virginia who hallucinated for 11 days after eating it in the 1600s. Even today, thrill-seeking young people regularly find themselves in the E.R. (or the morgue) due to datura poisoning.

Datura growing outside Loughborough Barn at Oak Spring.

While shamans, priests, and healers throughout the world have used datura flowers for ceremonial and medicinal purposes for centuries, the plant’s uses have also been more nefarious. Devil’s Breath or scopolamine, a drug made primarily from the seeds of flowers in the daturae tribe, has the reputation of reducing imbibers to a Zombie-like state and has been linked to countless crimes. Since datura is easily found growing in backyards and along roadsides, we recommend keeping children and pets well away from its pretty pin-wheel shaped flowers.

Godzilla weed (Reynoutria japonica)

Photo by Acabashi

Some of the prettiest ornamental plants - many brought across the seas by history’s unwitting botanists and landscapers - are the most destructive. Japanese knotweed is among them. It looks innocent enough with its tassels of white flower and heart-shaped leaves, but its nickname, “Godzilla Weed,” is well-earned. The tough invasive species, native to volcanic regions in Japan, has wide-spreading roots that can plunge to depths of 10 feet, crawling through the walls and foundations of buildings and tearing through roads and sidewalks. It causes millions of dollars of damage in the UK every year, and is on a similar path of destruction in the U.S.

The one good thing about this monstrous plant? It’s pretty tasty. The young shoots of Japanese Knotweed have been described as having a lemony, rhubarb-like taste, and can be used like rhubarb in pies, jams and chutneys.

Vampire Plants

Probably not vampiric, but the creepiest-looking winter squash growing at the Biocultural Conservation Farm: Black Futsu. Photo by Caitlin Etherton.

We know pumpkins are associated with all things spooky, but did you know that they (along with watermelons) are rumored to become blood-sucking creatures of the night? According to Balkan folklore, pumpkins or watermelons left too long in the patch - especially after Christmas - will transform into vampires, shaking, growling, and rolling into homes at night to “do harm to people.” The tale is a good reminder not to neglect your garden in the colder months!

Dodder. Photo: Brewbooks

More sinister than vampiric pumpkins are actual vampire, or parasitic, plants. They attach and feed off other plants using a structure called a haustorium which penetrates a host plant and transfers nutrients into the vampire plant, often weakening or killing the host. While there are thousands of species of vampire plants, among the scariest are dodders, or devil’s hair. Recent research has suggested that the twining stems of this plant can control the cell function of the host plant through the exchange of genetic information - just as sinister as the monsters they are named for.

wolfsbane (Aconitum)

Johanna Helena Herolt (1668-1721). Maltese cross (Lychnis chalcedonica), Monk’s cap (Aconitum napellus) and insects.

Monkshood or wolfsbane (so named because it was historically used to poison animal bait) has made appearances in legends, folklore, and literature from the tales of ancient Greece up to the pages of Harry Potter. Native to mountainous regions in western and central Europe, most species of the plant contain the highly toxic aconitine, which, according to Greek mythology, first dripped from the mouth of the hell-guarding three-headed dog Cerebus. Since ancient times, the poison has been used to coat swords and arrows in battle, execute criminals, and commit murder. In the medieval ages, it was said to be one of the key ingredients in Witch’s Ointment, which will make a broom fly when applied to the handle. While aconitine is still used medicinally today (not always with the desired results), wolfsbane’s most well-known use is as a repellent for werewolves and vampires.

If you do decide to use wolfsbane to ward off the supernatural this Halloween - or just to add some deep purple to your garden - be sure to wear gloves; gardeners have died from handling the plant.

Red tide algae bloom

Photo by Melvil

Thought to have inspired the biblical river of blood, red tide is a real phenomenon that is just as scary as what Moses unleashed on the Nile back in the day. A red tide occurs when a population of dinoflagellates algae explodes, creating an algal bloom. Perhaps you’ve seen the apocalyptic images of dead sea life crowding beaches in Florida from a 100-mile red tide a couple years ago; the culprit in that case was an alga called Karenia brevis, which causes gastrointestinal and neurological problems when consumed by fish and other sea life, killing them or leaving them comatose. While red tides have been occurring in the world’s oceans since humans were around to notice them, researchers have noticed an increase in recent years, suggesting that rising global temperatures could be to blame.

Tobacco (Nicotiana)

French School, Collection of botanical studies. c. 1820

Ornamental flowering tobacco growing in Oak Spring’s formal garden.

No list of monstrous plant would be complete without one of the deadliest plants in the world. Tobacco, most species of which are native to the Americas, is responsible for seven million deaths per year; the plant contains high levels of the toxic alkaloids nicotine (a highly addictive stimulant) and anabasine. While eating it can be fatal and handling it without proper protection can cause severe illness, the cured leaves have been widely used for smoking, snuff, and chewing for centuries. Even though consuming tobacco this way won’t kill you outright, tobacco use has been linked to many types of diseases and cancers - so it’s best to just use this pretty plant as an ornamental.

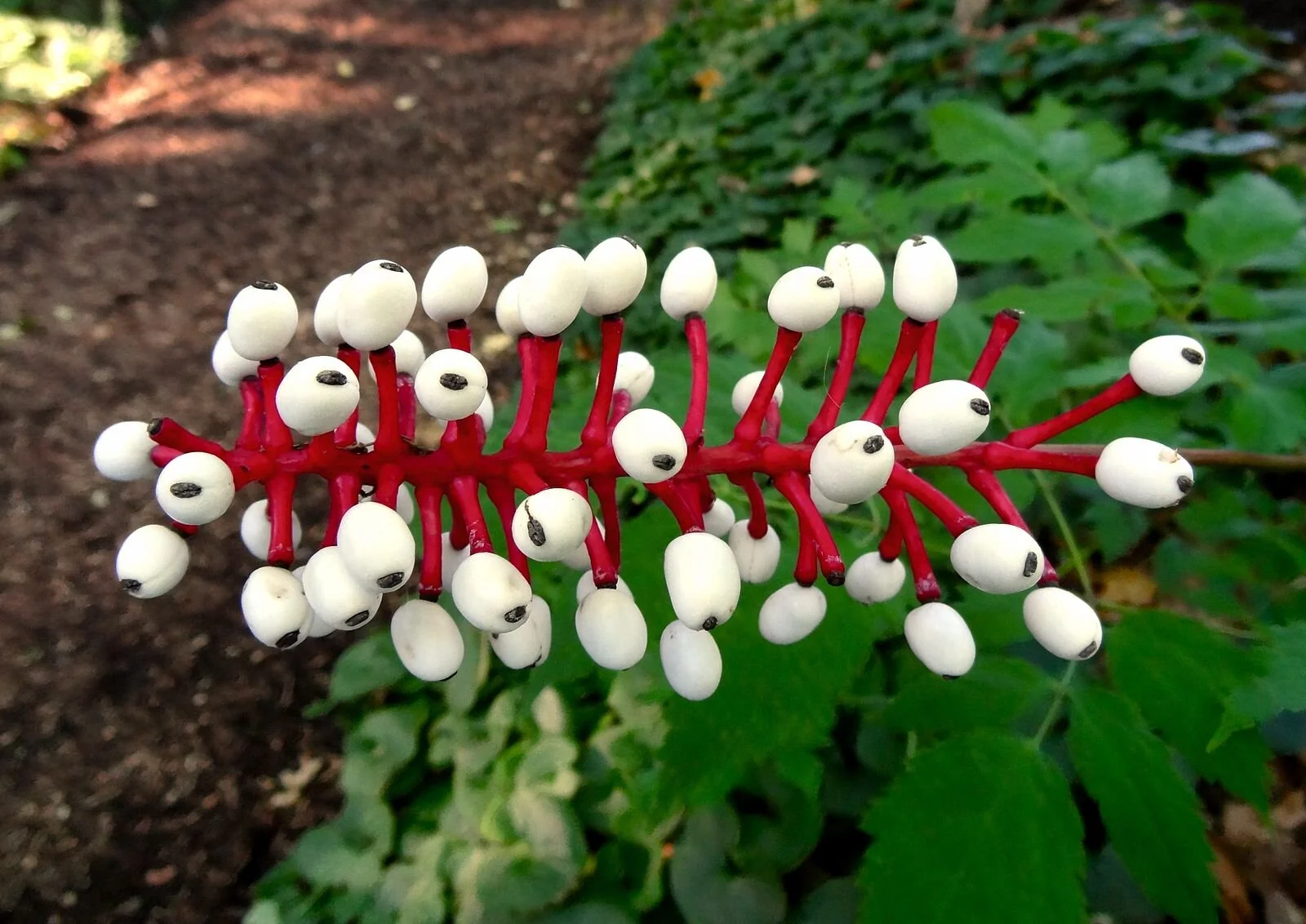

Doll’s Eyes (Actaea pachypoda)

Photo by Rizka

Aside from being incredibly creepy-looking, Doll’s Eyes - an herbaceous perrennial native to North America - is extremely poisonous. The plant contains cardiogenic toxins which have an immediate sedative effect on human cardiac muscle tissue, leading to cardiac arrest and death if enough berries are ingested. Oddly enough, several bird species can safely eat the berries and disperse the plant’s seeds. While reports of Doll’s Eyes poisoning humans are rare (probably because most people know better than to eat a plant that resembles eyeballs skewered on bloody spikes), the roots of the plant have been used in teas to treat menstrual cramps and pain associated with childbirth in the past.

Castor bean plant (Ricinus communis )

French School, Collection of botanical studies. c. 1820

Castor in Oak Spring’s garden. Photo by Judy Zatsick.

The next time you order a bottle of castor oil to soothe that dry cold-weather skin, remember that you’re moisturizing with a plant that produces one of the deadliest poisons in the world. Ricin, a toxic protein which can be derived from the waste material leftover from processed castor beans, infects cells, blocking their ability to synthesize their own protein and causing key functions in the body shut down in a highly unpleasant way. Because ricin is relatively easy to make and even a tiny amount is fatal, forms of the poison have been tested for by the United States for use as a biological weapon and have been used for assassinations and terrorist attacks. While bright-red castor plants are lovely and botanically fascinating (visit our new Fantastic Flora website to learn more), take care not to ingest the seeds if you add this plant to your garden.

Arbol de la muerte (Hippomane mancinella)

Photo by Hans Hillewaert

The arbol de la muerte (Tree of Death), which also goes by the less ominous “beach apple” or manchineel tree, is innocent enough in appearance - until you accidentally brush up against it or bite into its apple-like fruit. Found throughout the coasts of the Caribbean, Central America, the northern edges of South America, and Florida, the manchineel tree produces a milky white sap that causes burn-like blisters to appear on the skin and will likely cause temporary blindness if you’re unfortunate enough to get it into your eyes; the sap of this tree was likely used to coat the arrow that killed Ponce de Leon during his ill-advised 1521 trip to Florida. Worse, perhaps, is the excruciating oral pain (if not death) you will experience if you take a bit of the sweet-smelling apple, as this unfortunate vacationer discovered.

Special thanks to the Oak Spring Garden Library team for their help with this blogpost!