Alexander Wilson: America's First Birdman

Emily Ellis

The Oak Spring Garden Library collection, thoughtfully curated over decades by Rachel “Bunny” Mellon, houses some of history’s most significant books on natural history, many of them penned during times when humanity’s perspectives of wildlife and the environment were shifting dramatically. Among them is American Ornithology (1808-1814) by Scottish artist-naturalist Alexander Wilson - the trailblazing catalogue of North American birds you probably haven’t heard of.

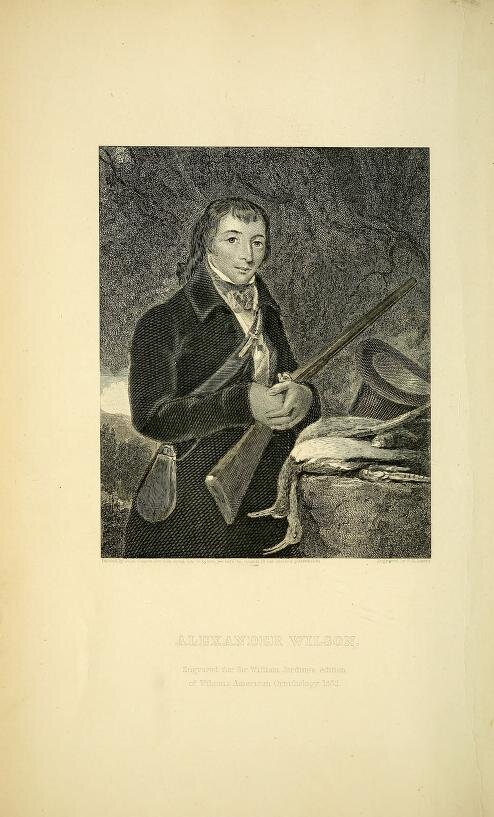

Alexander Wilson. Image from American Ornithology, http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/41411265, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library Blog

Wilson’s 9-volume Ornithology is considered the first such account of America’s birdlife, containing illustrations of 268 species and predating John James Audubon’s well-known The Birds of America by over a decade. Yet when it comes to artist-naturalists whose names are still synonymous with ornithology - Audubon, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, all the way up to David Sibley - Wilson is often left off the list.

Despite Wilson’s relative obscurity - likely due, in part, to the fact that he was not as gifted artistically some of his successors - he left his mark on conservation history. American Ornithology helped to educate people about diverse avian life inhabiting the shrinking American wilderness, and his accurate, scientific observations set a trend - and high standards - for future naturalists. The volumes of the work that exist in the Oak Spring Garden Library, as well as digitally in institutions like the Biodiversity Heritage Library, continue to help researchers and artists learn about America’s birds as they were seen by early ornithologists.

Wilson’s American Ornithology in the Oak Spring. Garden Library.

Alexander Wilson’s life was a dynamic one. Born in Paisley, Scotland in 1766 to a working-class family, he began working as a weaver at 13. Despite having left school at a young age, he was an avid reader and poet, much of his published writing focusing on worker’s rights and other social issues (and landing him with fines and prison time on several occasions).

Wilson immigrated to the United States in 1794, where he primarily worked as a schoolteacher in Philadelphia. He made time for trips and rambles into the wilderness to observe and sketch birdlife, for which he "had been biased, almost from infancy, for a fondness,” as he wrote in the introduction to American Ornithology. A friendship with famed botanist William Bartram encouraged him to move away from poetry and focus instead on illustration and natural history, leading Wilson to propose a multi-volume, subscription-based catalogue of the country’s birds.

While Wilson declared in the book’s introduction that “lucrative views have nothing to do in the business” - and indeed, procuring sufficient financial backing for the ambitious project was always an issue for him - the price of a subscription ($120, over $2,000 by today’s standards) limited it to several hundred wealthy individuals. Yet there was significant interest in the project: as colonies continue to expand westward, displacing Native American populations, the exploration of the continent’s wilderness was seen as an act of patriotism. Works of natural history, including Wilson’s, capitalized on this idea, and didn’t acknowledge the risk that rapid settlement posed to the wildlife species they were documenting. Unlike naturalists of today, Wilson also displayed a relative lack of concern for the birds he documented, killing and stuffing them to pose for his illustrations.

Despite its flaws, Wilson’s work was an impressive achievement. He completed most of the volumes in just seven years, traveling over 12,000 miles by foot and boat throughout the eastern states and territories. For the most part, his illustrations and accounts of bird behavior and ranges were detailed and scientifically accurate. While most naturalists of the time based their descriptions on dead specimens, Wilson made careful observations of birds in life, recording their nesting habits, diets, songs, and other details. His skill as a writer shines through in American Ornithology, which is peppered with poems and tales of his bird-hunting adventures, such as the story of the captured ivory-billed woodpecker that nearly pecked its way out of his hotel room in North Carolina.

Over the course of his research, Wilson would describe 26 birds previously unknown to scientists, and was also the first ornithologist to use the Linnaean system of naming to classify bird species. Today, five birds - Wilson’s snipe, Wilson’s warbler, Wilson’s plover, Wilson’s phalarope, and Wilson’s storm-petrel - carry his name.

Alexander Wilson peppered his scientific descriptions of birds in American Ornithology with verse. Image from The Biodiversity Heritage Library. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/175530#page/77/mode/1up.

Wilson’s legacy also lives on in the better-known ornithology he inspired. He wrote of meeting John James Audubon during the course of his travels, and while he couldn’t persuade the cash-strapped young bird enthusiast to subscribe to American Ornithology, most Audubon researchers agree that the meeting planted the seeds for Audubon’s monumental The Birds of America.

Wilson died before he saw the publication of Audubon’s work, or the completion of his own. He was was working on the ninth volume of Ornithology when he passed away from dysentery and exhaustion at the age of 47 in 1813, leaving his friend George Ord to complete the final book.

Although his uncompleted work would be overshadowed by later bird catalogues, Wilson remains a pioneering figure in natural history, laying the groundwork for how ornithologists understand and document birds today. As modern conservationists and birders work to research and protect some of the country’s most vulnerable species, detailed records like Wilson’s Ornithology can provide valuable insight into the history of birds in America - and continue to inspire “fondness” and concern for our country’s wildlife.