Judging a Book by Its Cover

Rachel Martin

In life we are always encouraged to never judge a book by its cover however for this blog, it’s book covers all the way down.

Book covers and more specifically book binding have come a long way. Now we are no longer beholden to the timeline of a monastic scribe, copying a text by hand or the revolutionary printing press. The methods and materials used for binding have also taken many forms to reach the modern books we know today. Read below to learn more about bookbinding throughout the years and view some of the examples held in the Oak Spring Garden Library collections.

![[H]ortus Sanitatis Venice, 1511 Contemporary wooden boards and blind-stamped calf, decorated with fleurons and geometric patterns. ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57d1b689e6f2e1faa4ced747/1674852064453-K9CQ2XBPTIEBOOB8MDLS/DSC_3690.JPG)

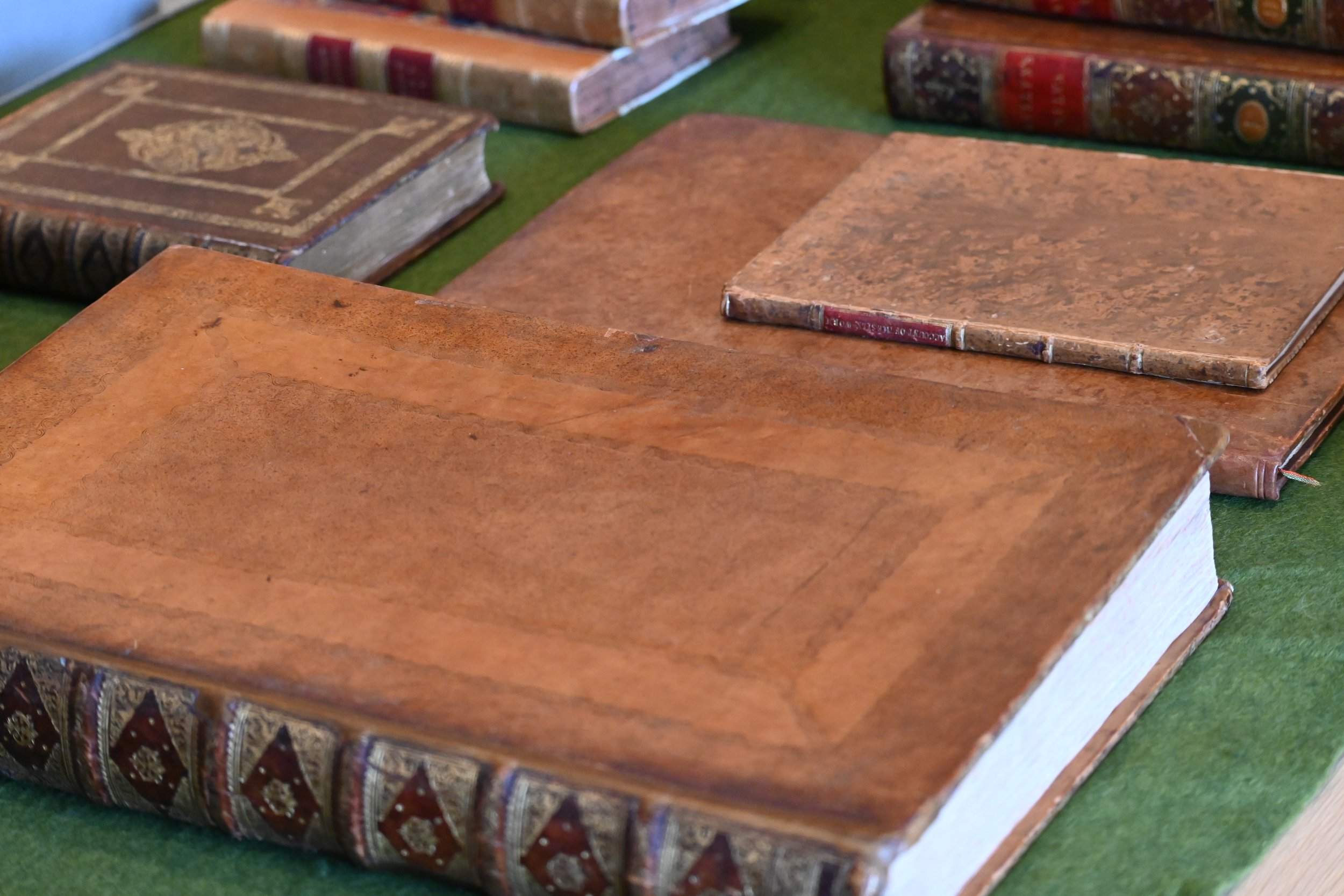

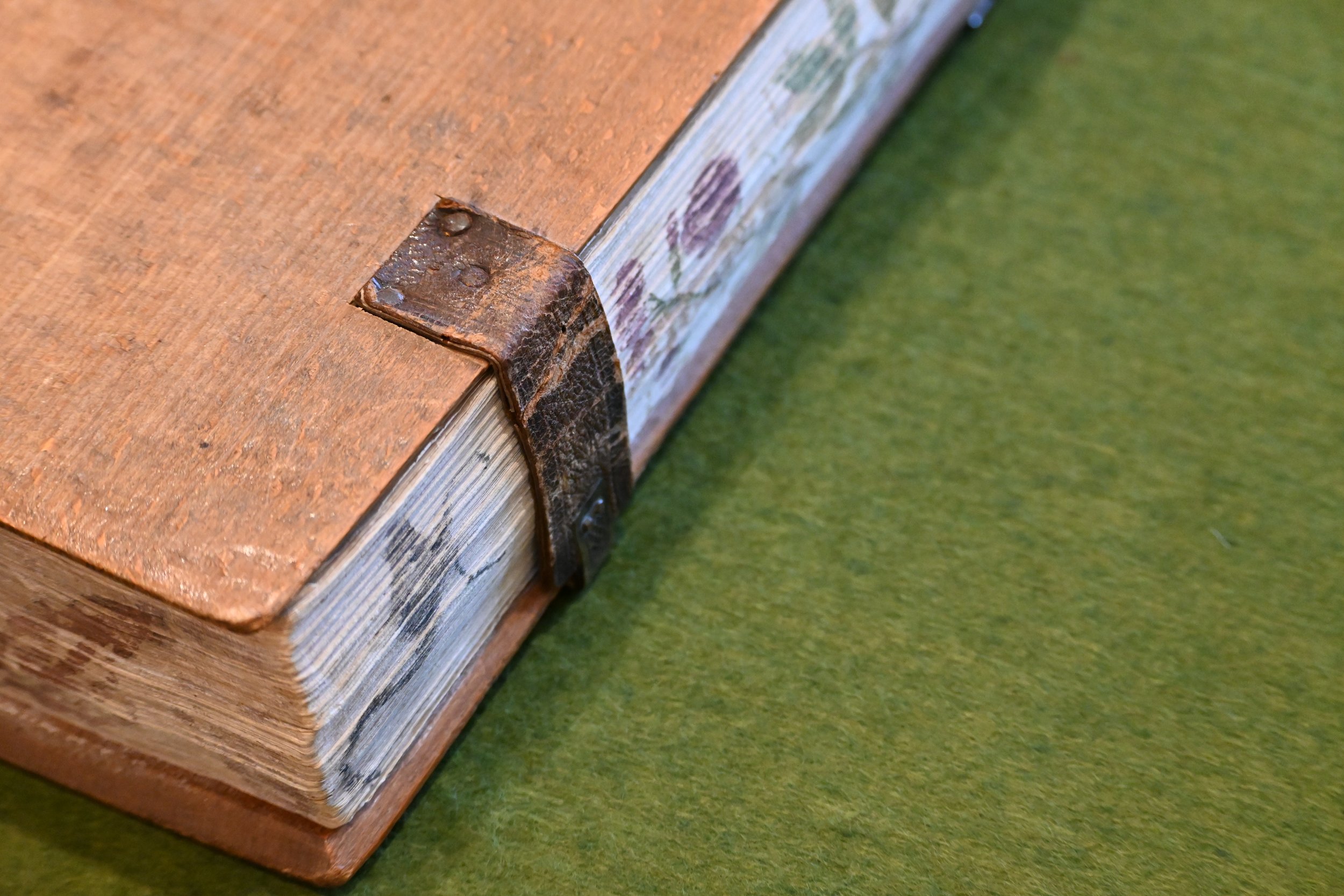

Before the advent of printing presses, books were largely reserved for aristocratic collectors and for monasteries. Early codices were bound by hand for most of the Middle Ages, the pages being gathered and sewn onto cords along the spine. The boards (or covers) were wooden, which varied in type depending on the region where it was bound. By and large most were oak and beech, which was widely available, and fastened with clasps.

Medieval “half binding” involved a sheet of leather that was pasted to the back of the book and pulled over the side of the book, to cover the joints of the board. Those quarter leather coverings ultimately gave way to full leather binding, where the boards were covered fully with leather, most prominently, tawed pigskin.

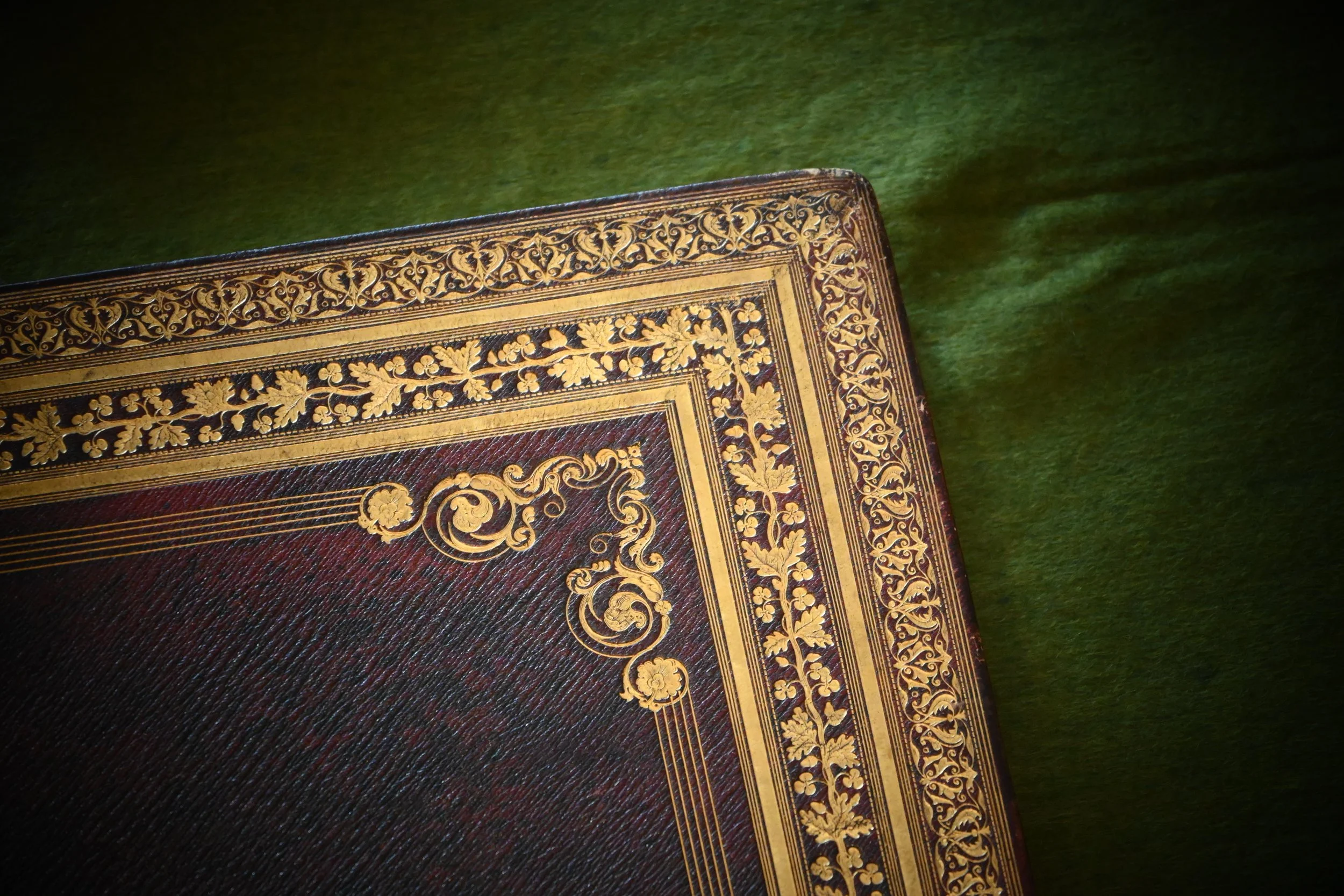

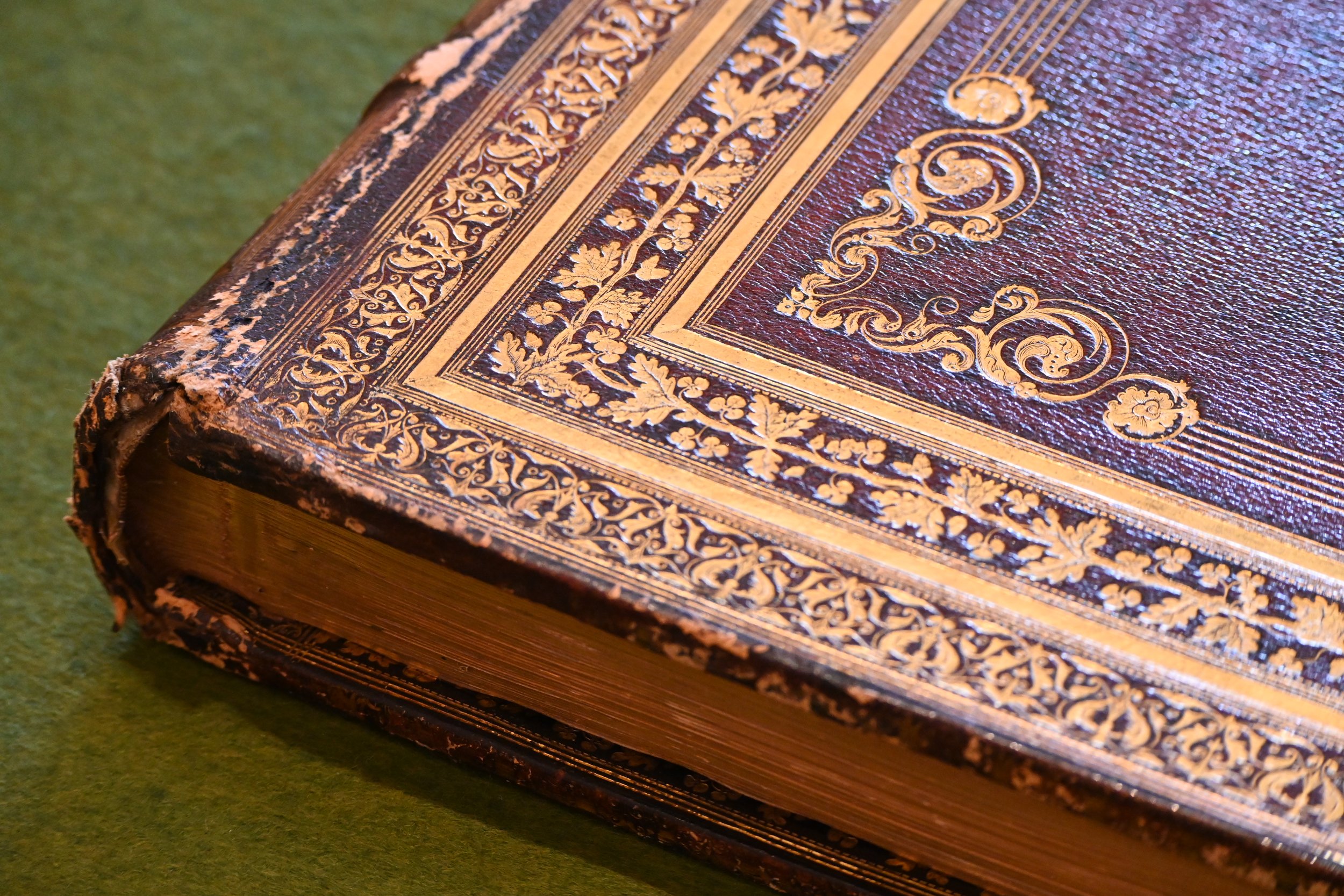

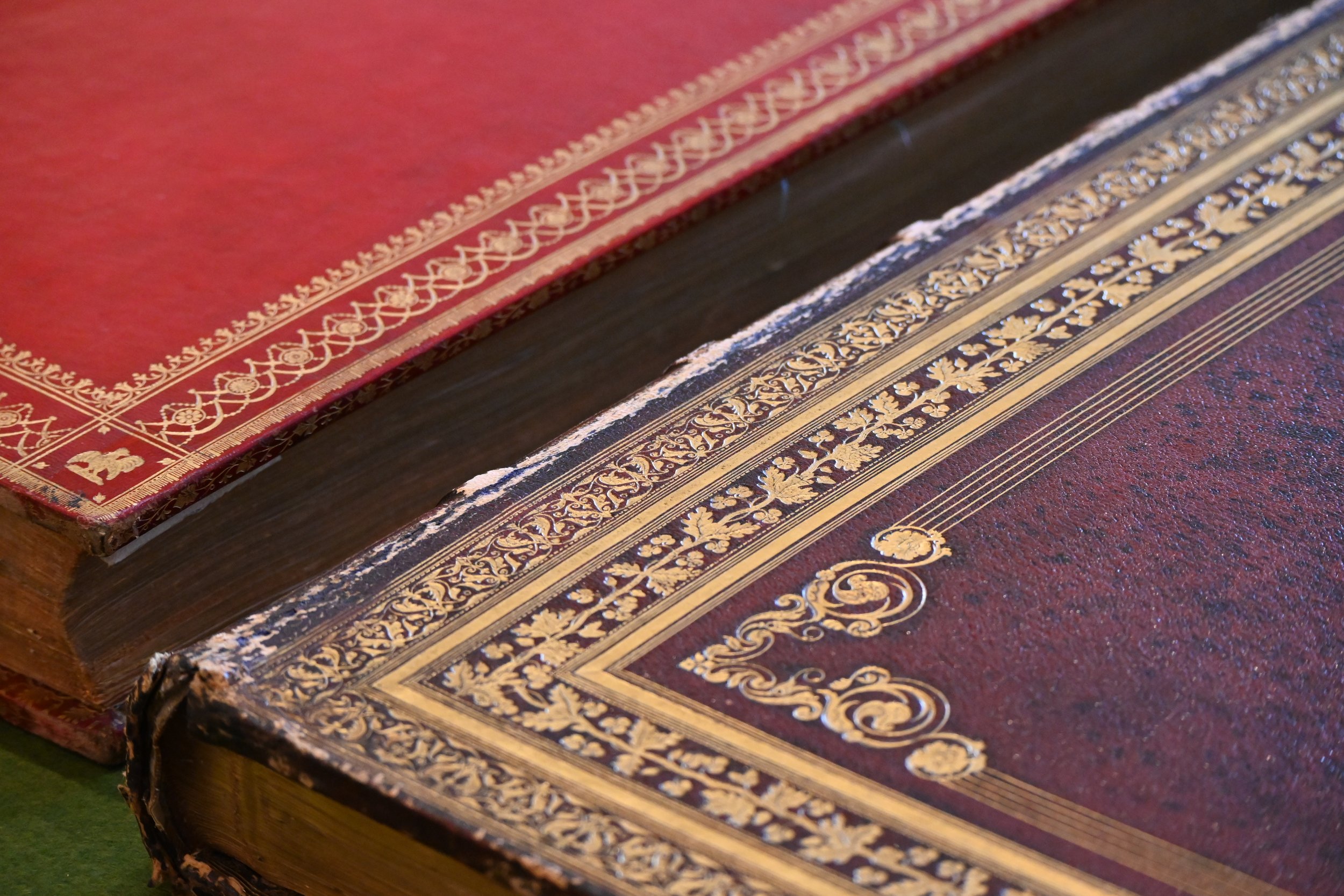

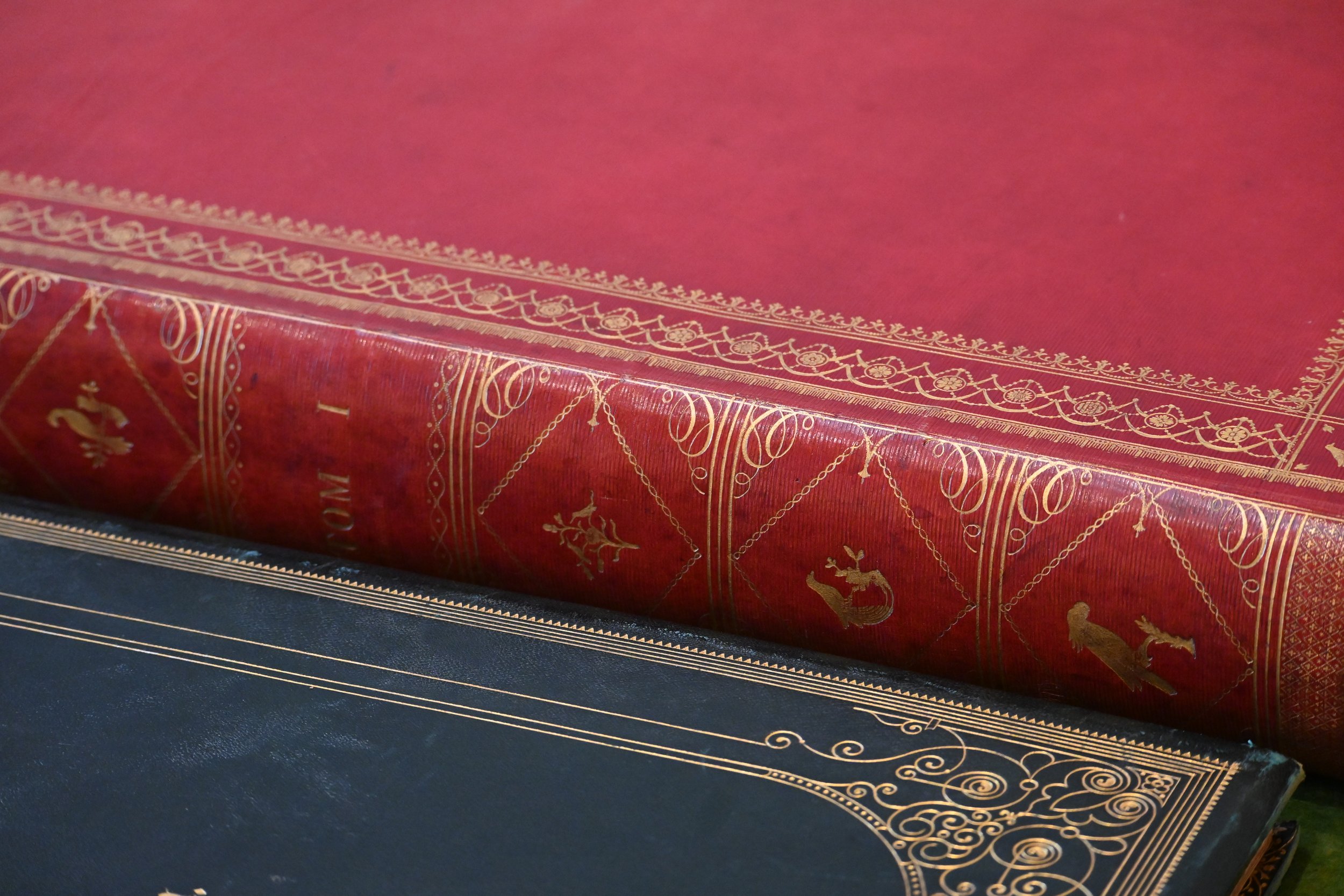

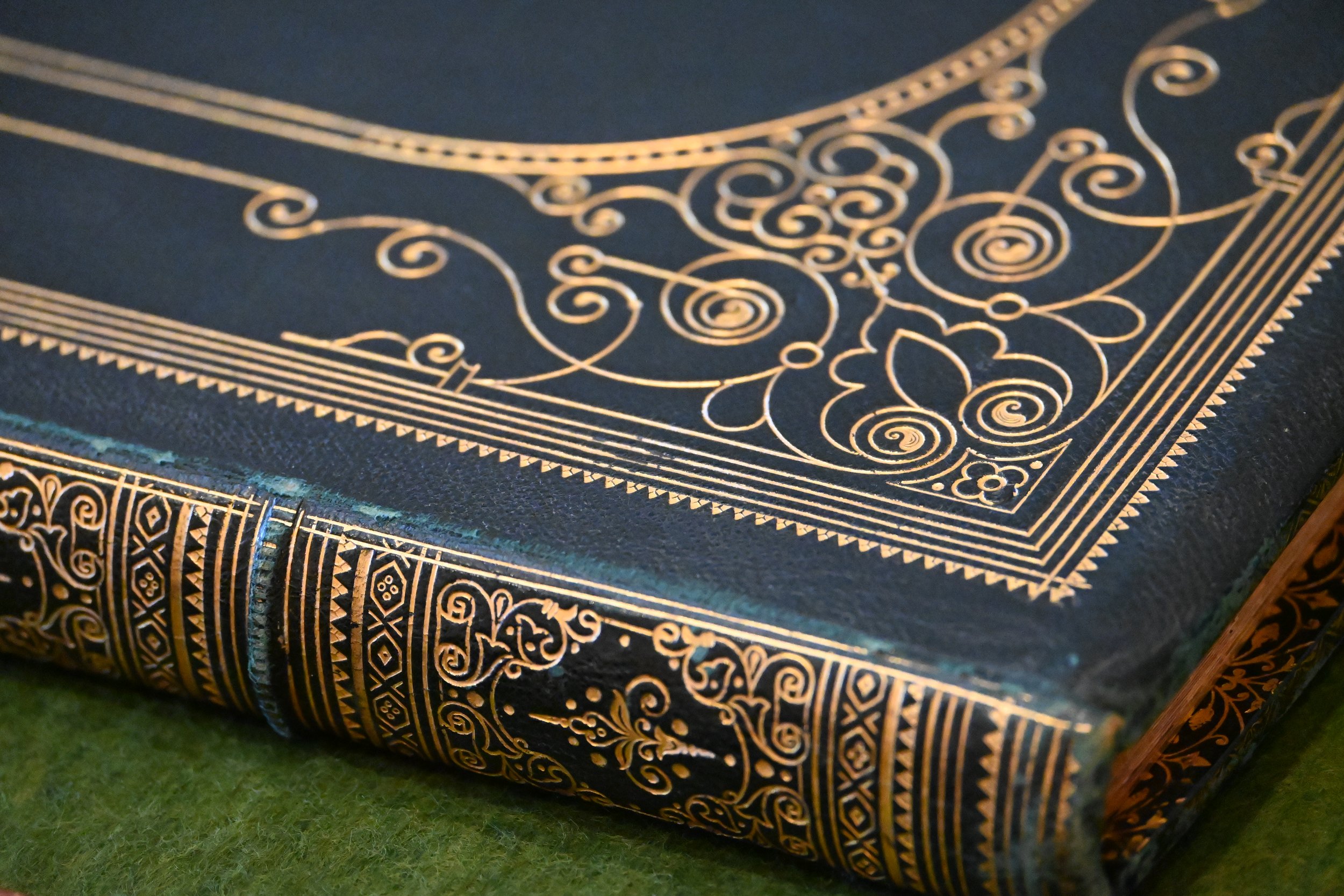

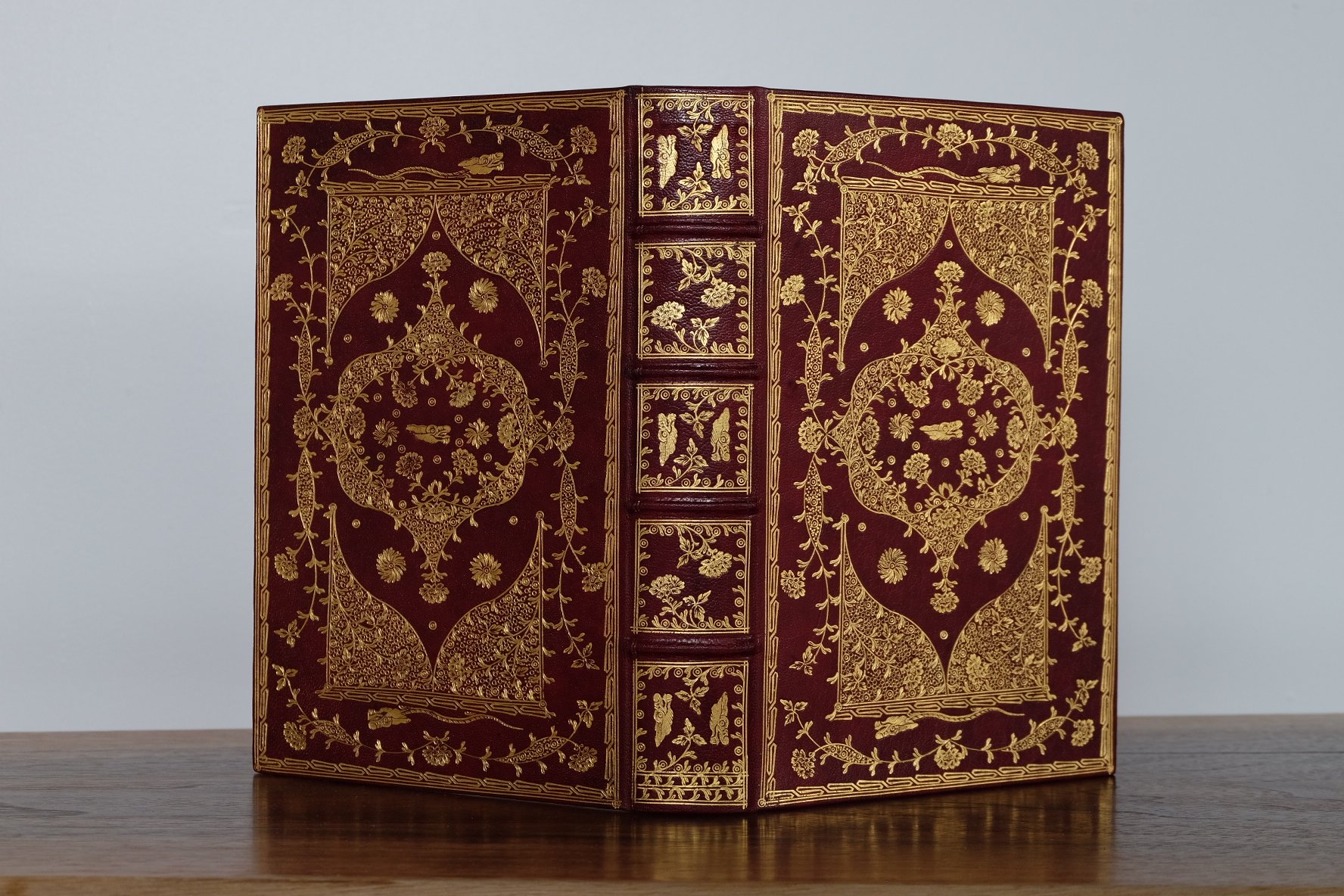

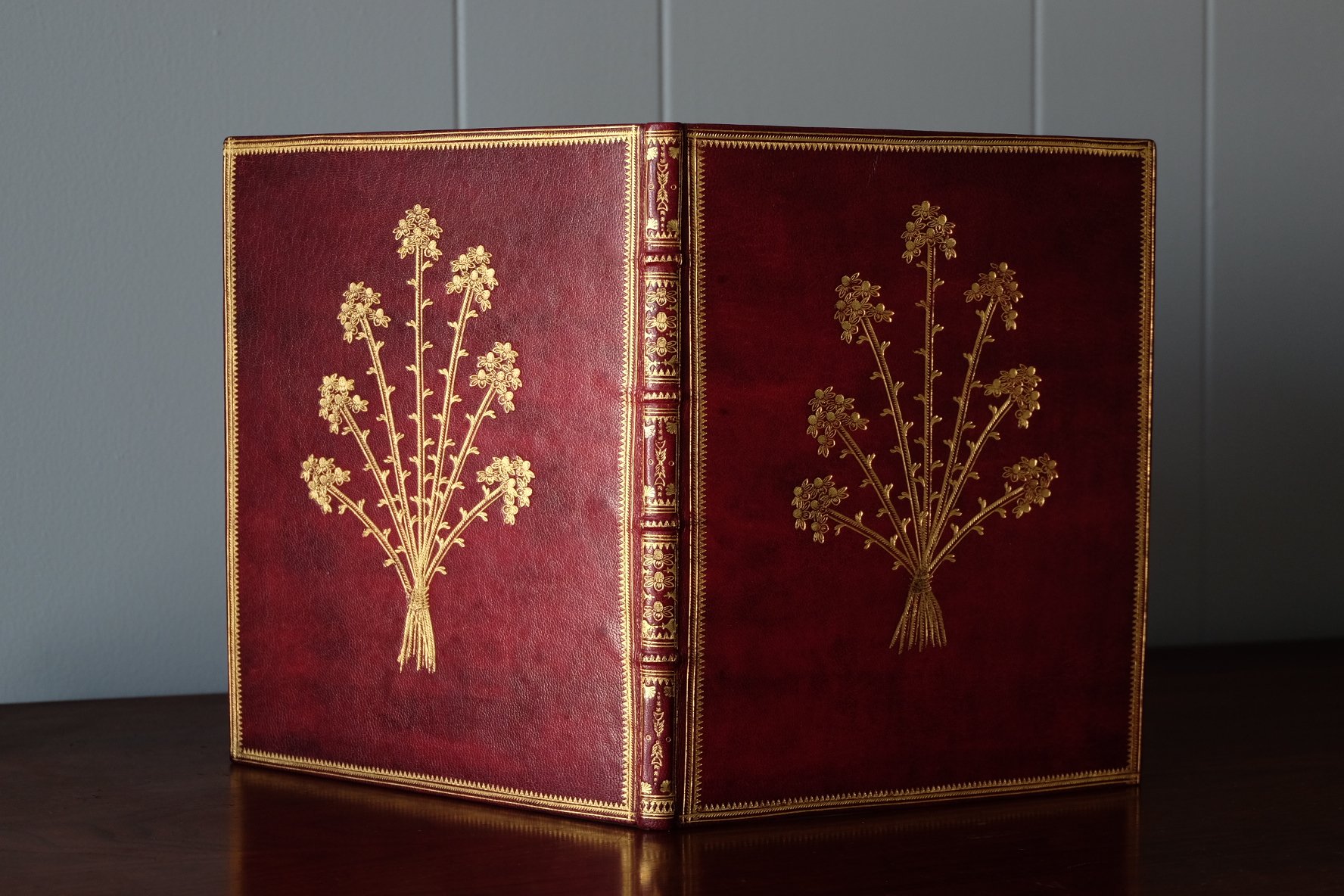

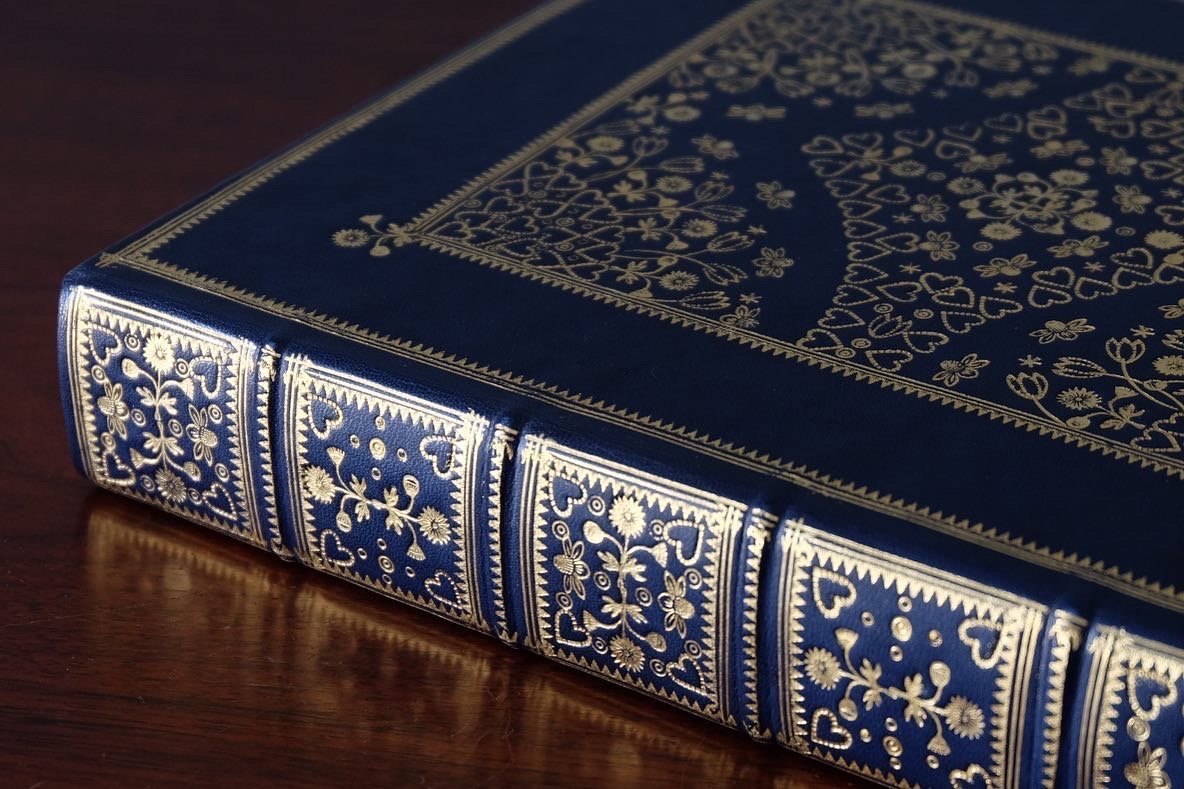

In recognizing the versatility and ease of vellum and other leathers, several specialized disciplines emerged during the early Renaissance for the purposes of decoration. One of which was the illuminator. The illuminated manuscripts – or “petit fers”, which is argued to first have been invented by the Moors – were the work of an illuminator who gilded gold or silver leaf over a sketched design on the book cover. These manuscripts could only be deemed illuminated if the use of gold or silver was used, which reflected light.

The material that came into popularity for these illuminated books and manuscripts was Morocco leather, commonly referred to simply as Morocco. This leather was extremely fine and had a smooth surface, which proved suitable for intricate gold tooling. The leather’s ability to absorb dye also made it popular and resulted in vibrant book covers. Other types of animal skin were also used: in Germany, pigskin was predominant; in England, calfskin.

The printing press, which utilized moveable type was first invented in Korea, some 200 years before the emergence of the printing press in Germany, which caused bookbinding in Europe to be transformed. Similarly, China had already seen the emergence of block printing during the Tang Dynasty, with the earliest example of a printed book being completed in 868 CE. In 1448, when the technology made its way through Europe via the Gutenberg Printing Press, the industry began to flourish.

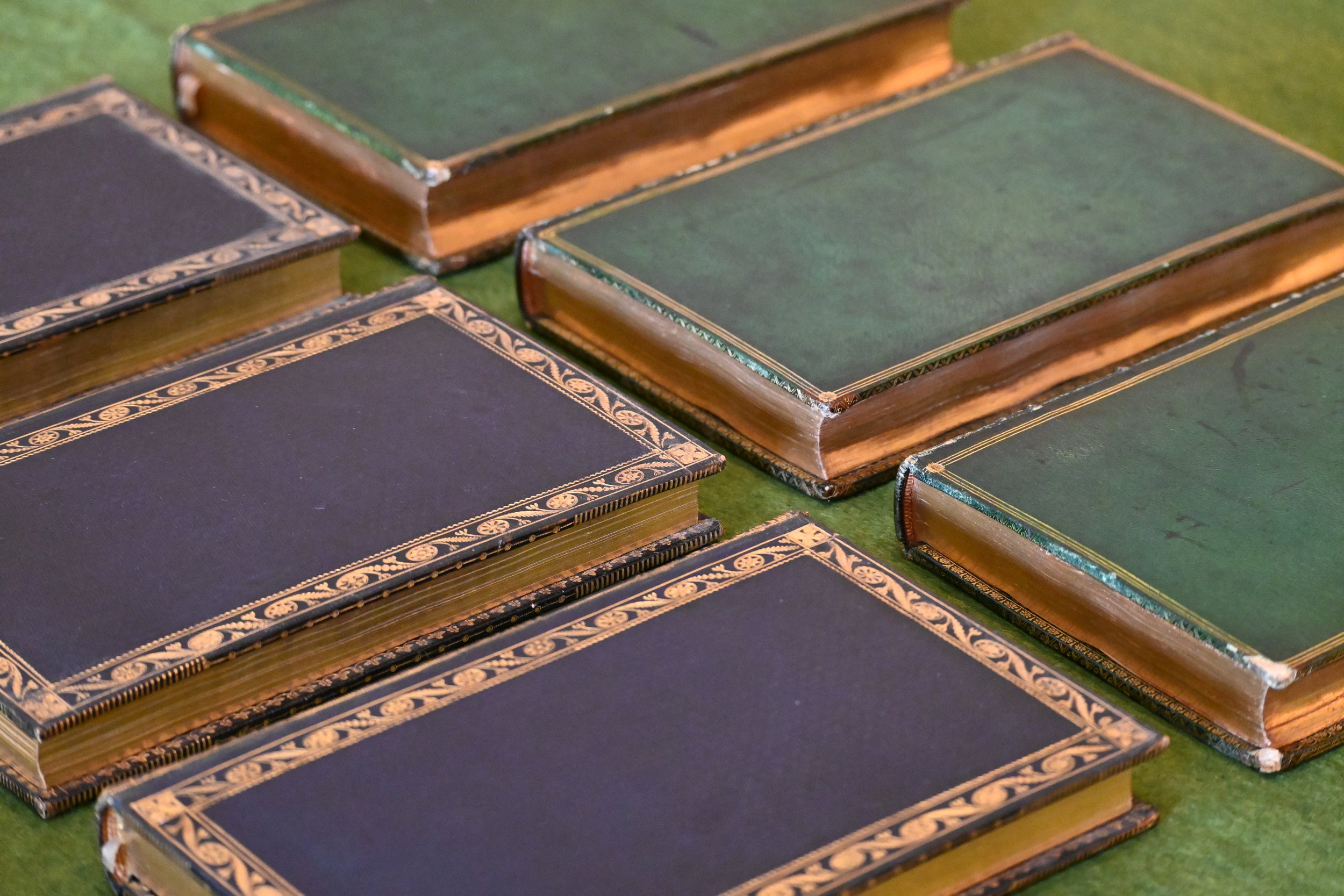

During the height of the Renaissance period, access to literature and books spread to the middle class. These books were steps away from the artful and crafted binding of the previous century. The use of vellum was common before, but became the predominant material to meet the mass of books being printed.

This trend continued up through to the 1850s, coinciding with the Industrial Revolution. In the height of the Revolution, old paper from previous binding projects was reused so as not to waste any materials. In fact, x-ray scans revealed materials and pages from manuscripts dating back to the Middle Ages being used in binding. The adoption of cloth coverings took the place of leathers and with it new conditions were created for efficiency and increased production to meet high demands. Namely “casing” which was the new term coined for books bound by a machine.

Antoine-Augustine Parmentier (1737-1813). Le Parfait Boulanger. Paris, 1778. Contemporary blue paste-paper wrappers.

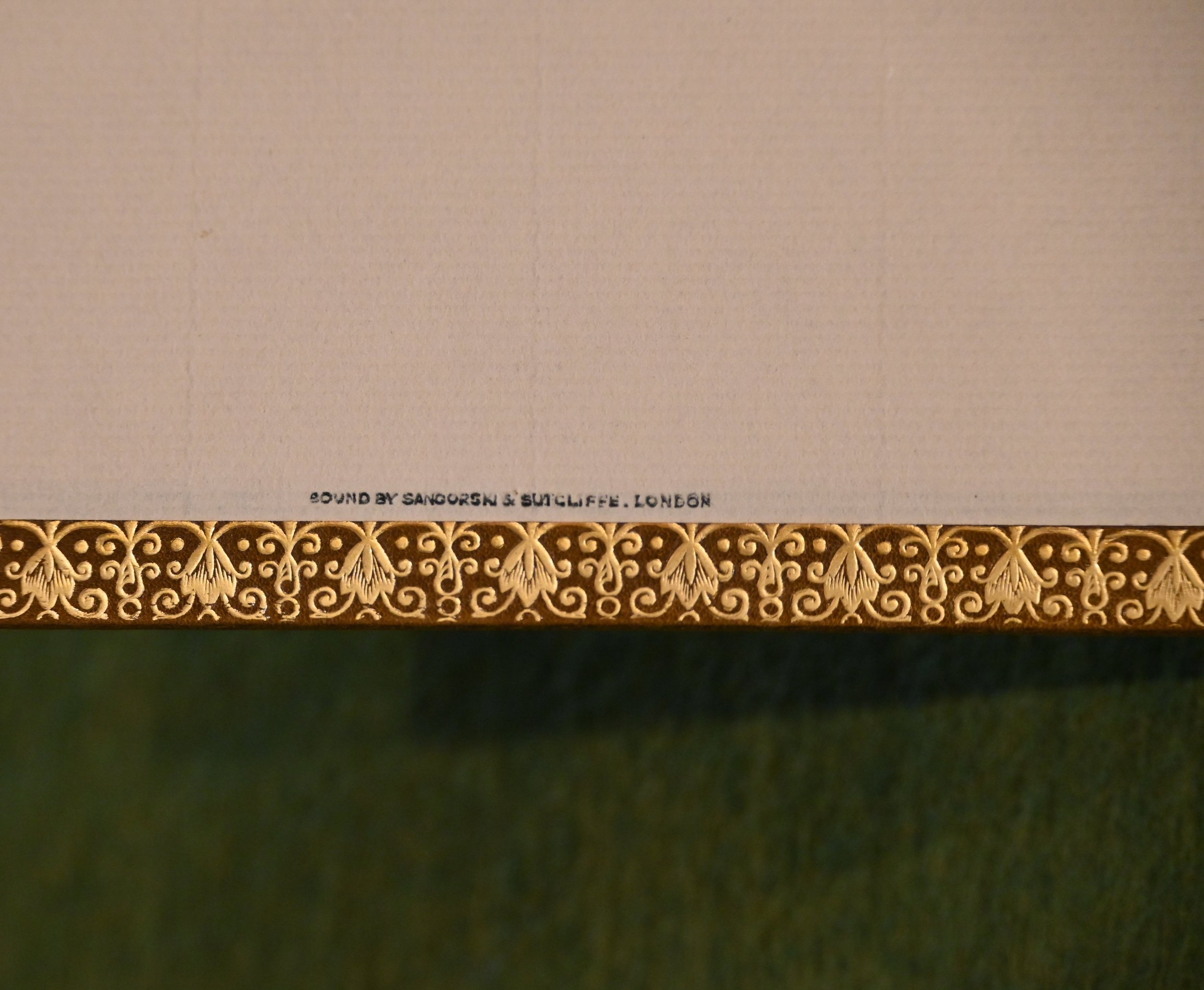

The outlandish and more detailed illuminated books didn’t fade away entirely, and in fact made a resurgence at the turn of the 20th century. One of the most prominent bookbinders responsible for this resurgence at this time was Sangorski & Sutcliff. The story goes that Francis Sangorski and George Sutcliff met in 1891 during a bookbinding class. Fast forward to 1901, when they founded their own bookbinding company, which quickly became one of the popular bookbinding companies of their time.

For a modern perspective on bookbinding, we caught up with Brien Beidler, who spent five weeks at Oak Spring in 2021 during an Interdisciplinary Residency.

“I’ve always been interested in books,” said Brien, a bookbinder and toolmaker based in Minneapolis Minnesota. “I thought older books were really beautiful [...] My grandparents had a few and I would always look at them and just think, ‘wow this is so gorgeous, I wonder how it was put together.’”

This interest was further cemented during a highschool art class, where Brien was tasked with tearing apart a book to make a sculpture. “I specifically remember thinking, ‘I want to do the exact opposite of that,’” Brien said.

Fast forward to his time at the College of Charleston where he was introduced to Marie Ferrara, Head of Special Collections, who offered to teach him bookbinding. From there it was history. Some modern binders utilize modern materials and experiment with binding techniques. Brien, however, keeps his approach similar to the pre-industrial times of bookbinding, before mechanized tools transformed the process in the early 19th century.

“I really like historic-looking books [...] so I try to stick to the materials that were used in the historic examples,” Brien said. Brien does all the steps from folding every sheet of paper to putting intricate designs on the binding. Brien hand engraves his own metal stamp-like instruments to use for tooling, the process which creates beautiful embossed symbols on book covers.

![“I was really inspired by a lot of the books in the collection […] I would engrave these little plates based off of some of the plant specimens I was seeing.” -Brien Beidler](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57d1b689e6f2e1faa4ced747/1674945916489-G2AQ13D3IYTP12M2F866/183349B2-0DCA-4167-9193-8540187D6C81-1402-00000303B42D0D73.JPG)

“Traditionally they were made out of bell bronze,” Brien said. “So I spent most of my time at Oak Spring working on casting the blanks for these tools and then hand engraving those.”

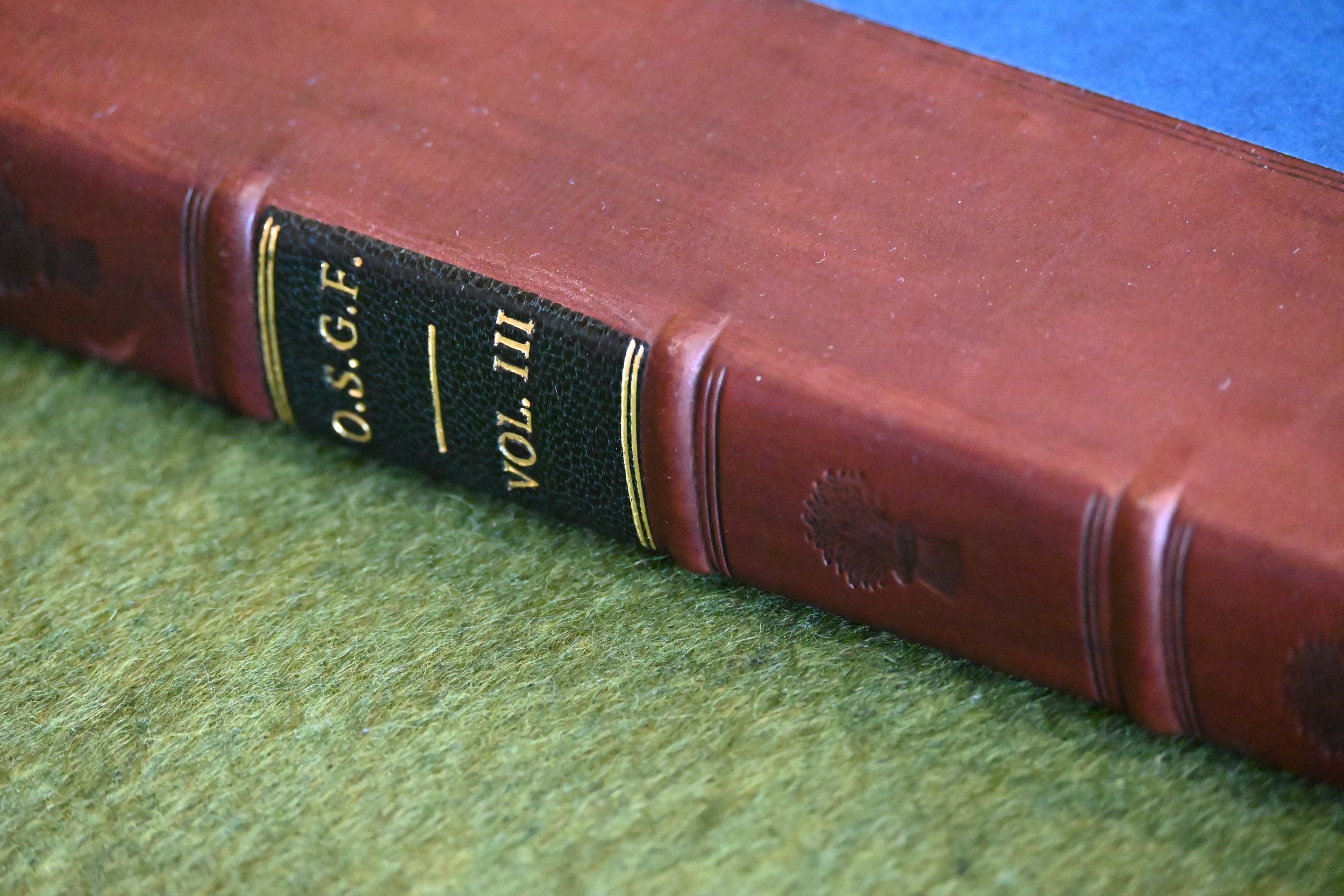

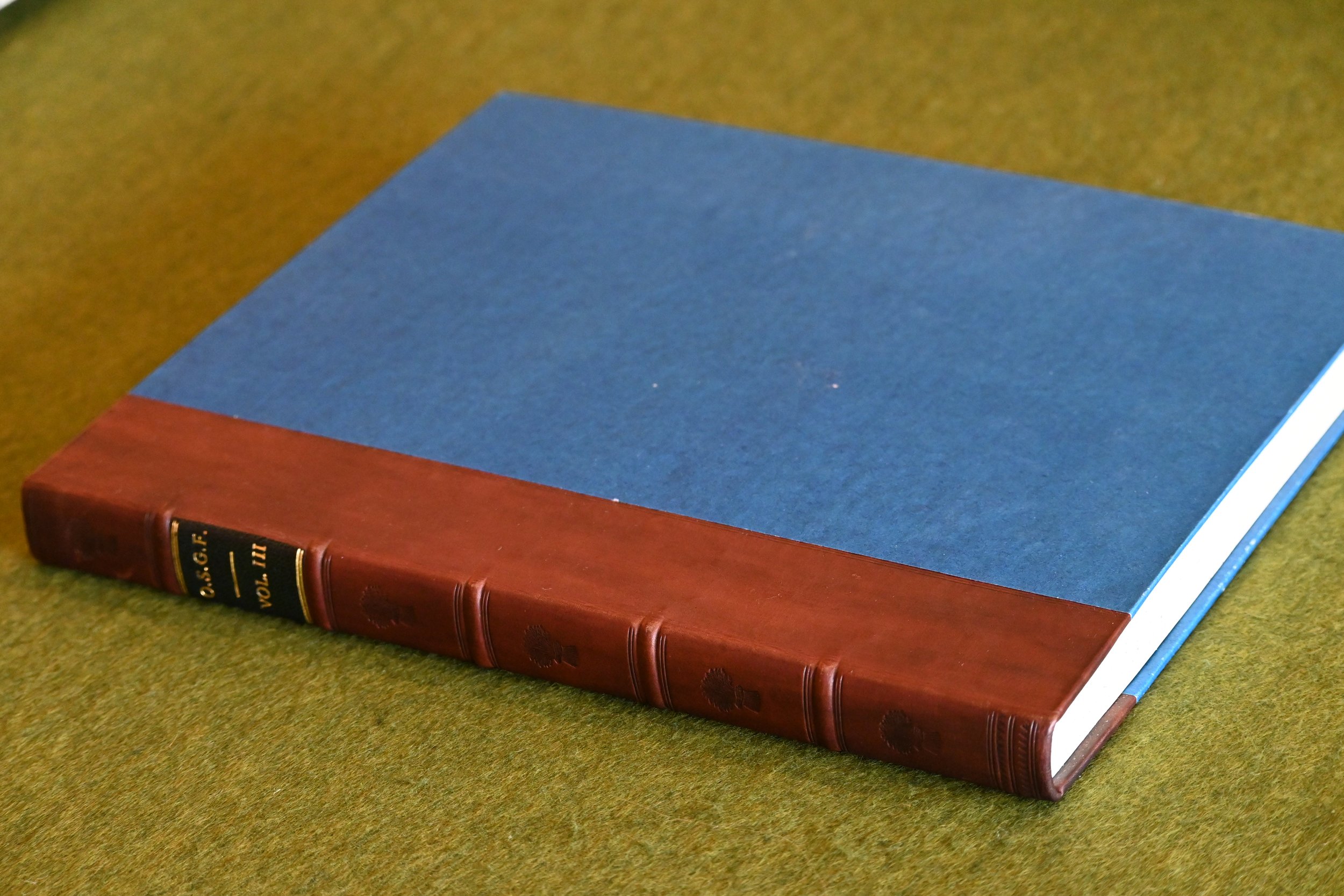

During his residency, Brien worked on developing the alloy he now uses for these tools. He is also working on a 10 volume set of guestbooks, each with a unique design from images of Oak Spring. One volume, which resides at the Oak Spring Garden Library, includes Mr. Paul Mellon’s seal in the tooling on the spine, and utilized papers from Mrs. Mellon’s collection.

The collections at the Oak Spring Garden Library have no shortage of inspirations and examples of Medieval to modern binding approaches. Several of Mrs. Mellon’s books are housed in modern paper boxes for protection and decoration. One unique example of this is displayed in the binding of the book about potatoes, which was also bound in a potato feed sack.

![André Jacob Roubo (1739-1791). L’Art du Treillageur, ou Menuiserie des Jardins. [Paris], 1775. The slip-case of half vellum and marbled boards was made for this rare book which was a favorite of Mrs. Mellon.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57d1b689e6f2e1faa4ced747/1674853109688-7AVWF1FOHCUO47794LMG/DSC_3725.JPG)

“I was really inspired by a lot of the books in the collection,” Brien said. “I was just fascinated by the illustrations and I was so charmed by them that I would engrave these little plates based off of some of the plant specimens I was seeing.”

The prospect of keeping with old traditions in an increasingly technological age doesn’t deter him. “I just don’t think that everybody is willing to give up that format of sharing and experiencing information,” Brien said. “It’s still a useful technology, so to speak.” In fact, someone might even be more willing to appreciate and purchase a handbound book, because of what’s at our fingertips. And for those whose interest is piqued? He recommends Philobiblon and The Guild of Bookworkers. “You can ask people questions, they also have a lot of lists of resources” Brien said.

Thank you to Brien Beidler for offering up his time and insights for this post. Additional thanks to Head Librarian Tony Willis Thank you to Tony Willis for his insights into the OSGL collections.

References:

“3.2 History of Books.” Understanding Media and Culture, University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing Edition, 2016. This Edition Adapted from a Work Originally Produced in 2010 by a Publisher Who Has Requested That It Not Receive Attribution., 22 Mar. 2016, https://open.lib.umn.edu/mediaandculture/chapter/3-2-history-of-books/.

“Chapter 4: Bookbinding and Decoration.” Chapter 4: Bookbinding and Decoration | Incunabula, https://www.ndl.go.jp/incunabula/e/chapter4/index.html.

Alstrom, Eric. “16th Century: Birth of the Modern Book.” MSU Libraries, 2011, https://lib.msu.edu/exhibits/historyofbinding/16thcentury/.

Beidler, Brien. “Bookbinding Questions.” 24 Jan. 2023.

Diehl, Edith. Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique. Hacker, 1979.

Dr. Erik Kwakkel, "Medieval books in leather (and other materials)," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed January 24, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/medieval-books-in-leather-and-other-materials/.

McKinney, Kelsey. “Articles.” Ransom Center Magazine, University of Texas at Austin, 10 Dec. 2012, https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/2012/12/10/sangorski-and-sutcliffe-the-rolls-royce-of-bookbinding/.

Romney, Rebecca. “The Secret Language of Rare Books: Morocco - Bauman Rare Books.” Bauman Rare Books Blog, 14 May 2020, https://www.baumanrarebooks.com/blog/the-secret-language-of-rare-books-morocco/.

Sallay, Dóra. “The History of Manuscript Illumination.” V.1. Manuscript Illumination, Department of Medieval Studies at Central European University, http://web.ceu.hu/medstud/manual/MMM/frame17.html.

Images Citations:

Samuel Hartlib (ca. 1600-1662).The Reformed Common-Wealth of Bees.London, 1655. Rebound by Sangorski & Sutcliffe (London) in modern tan morocco.

Parmentier, Antoine Augustin (1737-1813) Examen chymique des pommes de terre : dans lequel on traite des parties constituantes du bled / par M. Paris Didot, 1773

Simon Bening (Flemish, circa 1483–1561). Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis ad usum Romanum. Illuminated manuscript on vellum.

[H]ortus Sanitatis.Venice, 1511.Contemporary wooden boards and blind-stamped calf, decorated with fleurons and geometric patterns. Fore edge painting of a Numidian crane, roses with leaves, and a lion by Cesare Vecellio (1521-1601), who was Titian’s nephew (Tiziano Vecellio, ca. 1488/90-1576).

Antoine-Augustine Parmentier (1737-1813). Le Parfait Boulanger. Paris, 1778. Contemporary blue paste-paper wrappers.

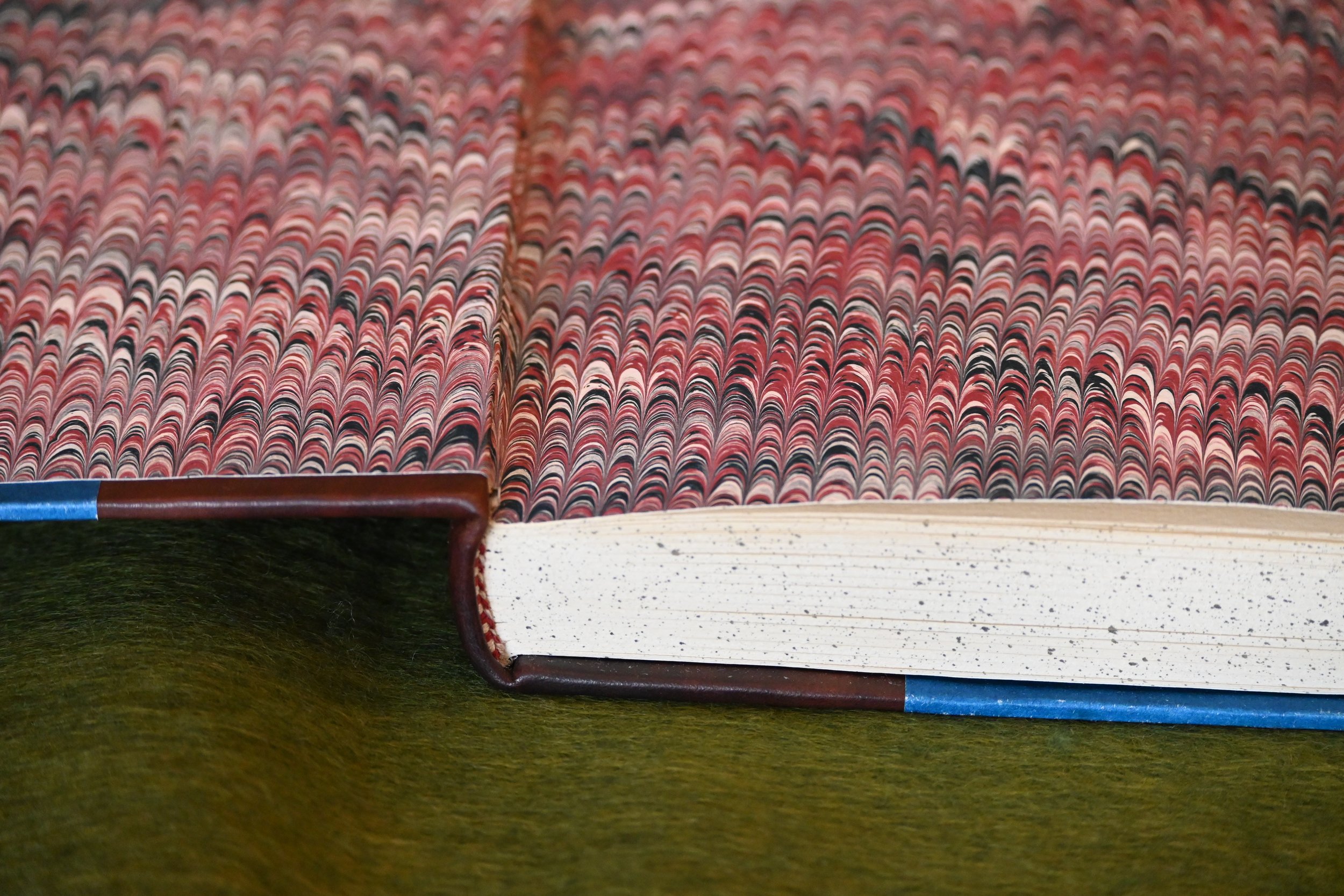

André Jacob Roubo (1739-1791). L’Art du Treillageur, ou Menuiserie des Jardins.[Paris], 1775.The slip-case of half vellum and marbled boards was made for this rare book which was a favorite of Mrs. Mellon.