Isabella Aiona Abbott: The First Lady of Limu

OSGF

Seaweed, kelp, macroalgae, whatever you choose to call it, can sometimes seem a little boring, but not to Isabella Aiona Abbott. A fascination with these plantlike organisms began in her youth and steadily grew into Isabella becoming the foremost expert in Pacific marine algae. As we recognize Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, learn about the life and contributions of the First Lady of Limu.

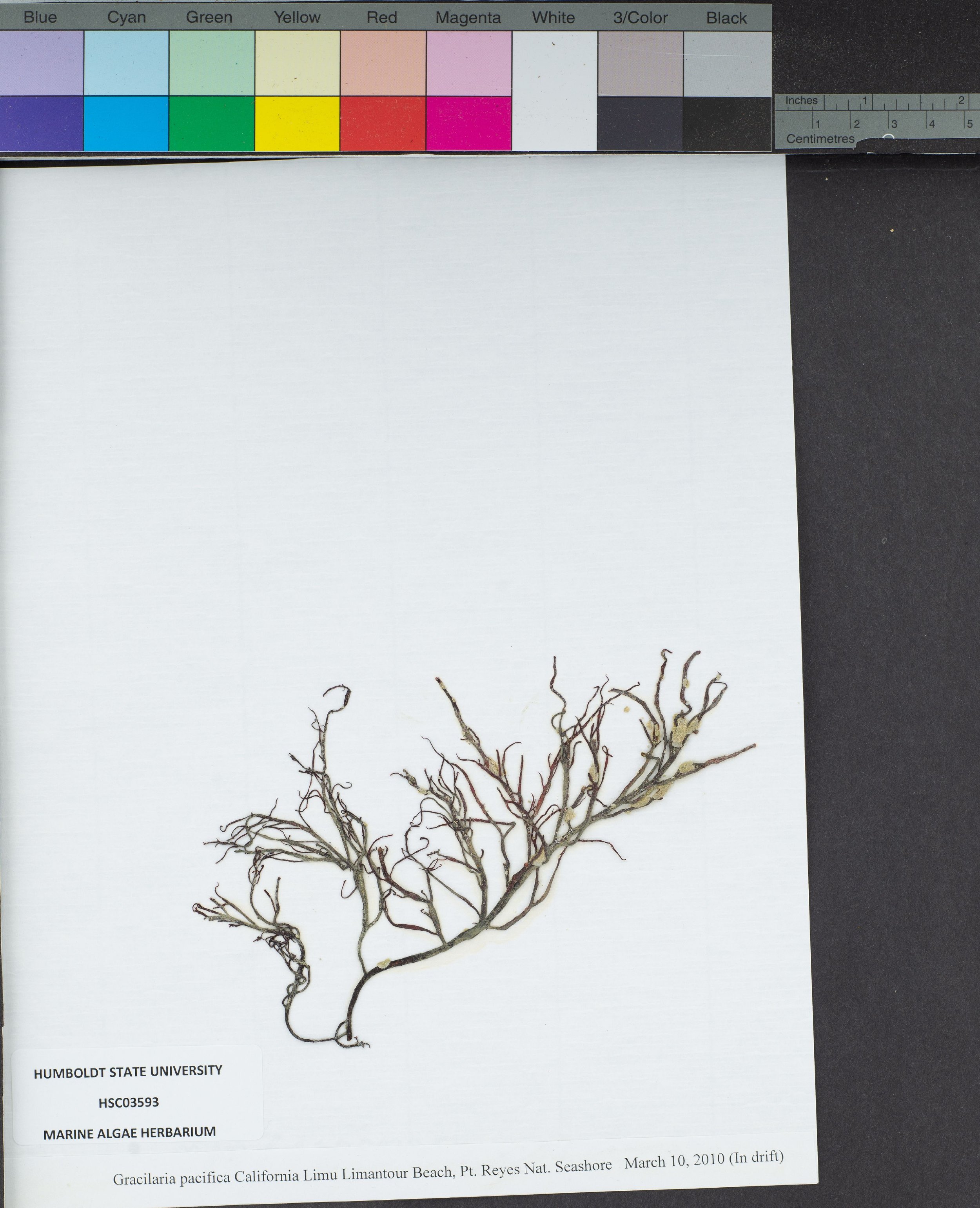

The beaches Isabella and her family would visit, where her limu education began. Photo c. 1920 via WikipediaCommons.

Isabella Abbott’s (born Isabella Kauakea Yau Yung Aiona) first introduction to seaweed was early. As the only girl among eight brothers she and her siblings were brought to the beaches of Hawai’i by her mother. There Isabella (fondly referred to as “Izzie”) amassed a collection of close to 70 species of seaweed and began learning about them; which ones were tasty, which were better fresh or cooked, and their Hawaiian names. In the salt and freshwater communities that populate the coast of Hawai’i’s eight islands, the plants and plantlike species that occupy those areas are described in the Native Hawaiian language as limu.

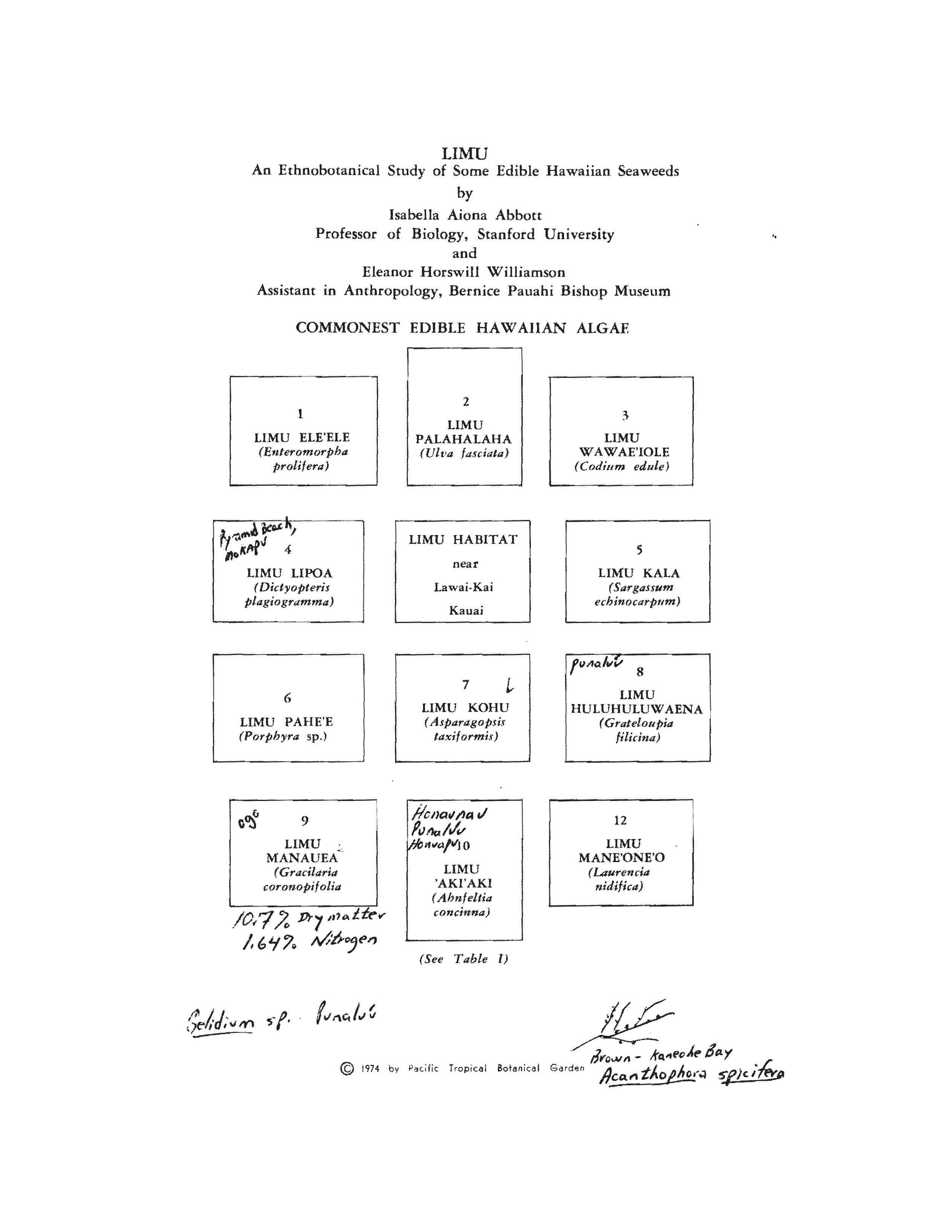

Limu is deeply embedded into Native Hawaiian culture. In the cultural ceremony of forgiveness, Ho‘oponopono (‘to make right’), limu kala is used by participants who, after having been forgiven, eat the limu. The second word, kala, has two meanings; one is to forgive or release, the other is rough which references the spined margins of Sargassum echinocarpum. Historically in Hawai’i it was the women who would harvest wild limu– this was due to kapu, a set of laws and regulations based in religion for men and women. For this reason, women became the knowledge-keepers of limu, which was then passed down to their children. “My mother knew every edible limu that was there” she once shared, “it was a knowledge system, she probably learned from her grandmother.”

With this introduction, the foundations for her lifelong career were continuing to be laid during her formal education. As an adolescent attending Kamehameha School for Girls, she and fellow classmates were tasked with taking care of the school garden every Wednesday. From there she went on to pursue an undergraduate degree in Botany from the University of Hawai’i in 1941 and just a year later, a masters in Botany from the University of Michigan. The A’s were aligned and thanks to alphabetical seating arrangements, she met Don Abbott in the university’s botany class— who she would later marry in 1942.

Both in their early 30’s and fresh out of school, the Abbott’s moved to California to attend UC Berkeley and fully cement their scholarly pursuits. After successful defense of her PhD in 1950, this made Isabella the first Native Hawaiian woman to hold a PhD in a scientific field. Recently graduated, the Abbott’s moved two hours south where they both began different positions at Stanford. Don had accepted a teaching offer (one of many) but because of anti-nepotism laws, which gave preferential treatment to men, the same offer wasn’t extended to her until almost a decade later, despite her equal qualifications. Through this Isabella became the first female full professor of biological sciences in the university’s history. During her tenure at Stanford, she and colleague George Hollenburg co-published a book on the marine algae of Monterrey, which described 55 new species. George even went as far as to name a new genus of algae Abbottella, meaning “Little Abbott”, in her honor.

After roughly two decades of teaching, eight books, and nearly 150 publications, she and Don retired and returned back to Hawai’i. Retirement for Isabella though simply meant new opportunities.

“[she] defined human relationships to the ‘āina (‘that which feeds’) as part of nature as opposed to outside of it.”

Her research continued to evolve as she turned her attention back to the stories and associations she was introduced to on the beaches as a young girl. Working as the Wilder Professor of Botany for her alma mater, the University of Hawai’i, she began revisiting the traditional ties limu had to Native Hawaiians. This work in ethnobotany went on for nearly 4 decades in her “post-retirement” phase as she encouraged students to study the links between native Hawaiian plants, offered hands-on experiential learning, and served up slices of her famous seaweed cake. As a result of her tirelessness, the University eventually went on to develop an undergraduate major in Ethnobotany that still receives students today.

Over the span of Isabella's life, the First Lady of Limu grew to be known as not only a scientific expert, but an enthusiastic mentor, and dedicated teacher. In her career she described over 200 new species of algae, including Peleophycus named after the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes Pele, due its resemblance to lava. In 1997, she received the Gilbert Morgan Smith Medal from National Academy of Science, the highest possible honor in the world of marine science. She was also bestowed with the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources. When Isabella was living and working in California she published the definitive 827-page book, Marine Algae of California, which continues to be cited today by botanists, marine biologists, and other researchers. In her second life as an ethnobotanist, she published Lā'au Hawai'i: Traditional Hawai'ian Uses of Plants, which was one the first comprehensive ethnobotany textbooks at that time.

Banner images: Photo of Isabella Abbott by Chuck Painter / Stanford News Service. Limu illustrations from the Library of George Balazs.

References:

“Isabella Aiona Abbott: 2001 Distinguished Economic Botanist: Interpreting Pre-Western Hawaiian Culture as an Ethnobotanist.” Economic Botany, vol. 56, no. 1, 2002, pp. 3–6. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4256514. Accessed May 2023.

Abbott, Isabella A. “The Uses of Seaweed as Food in Hawaii.” Economic Botany, vol. 32, no. 4, 1978, pp. 409–12. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4253984. Accessed May 2023.

Isabella Aiona Abbott interviewed on PBS Hawaii’s original series, “Long Story Short” with Leslie Wilcox. Original air date, June 17, 2008. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4qvIXFS5k-k

Jue, M., & PublishedApril 3, 2023. (2023, April 3). Invisible seaweed. Society + Space. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/invisible-seaweed

McGregor, L. W. (2019). Limu traditions. Hawaii Sea Grant. https://seagrant.soest.hawaii.edu/limu-traditions/

Wianecki, S. (2020, January). Hawai’i’s first lady of limu. Hana Hou!, (22). Retrieved 2023, from https://georgehbalazs.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2020-Hawaiis-First-Lady-of-LIMU-Hana-Hou.pdf.