Unsung Pollinators

OSGF

When someone says the word pollinator, what first comes to mind? You may think of a European honeybee moving from flower to flower, or the iconic monarch butterfly and its fiery orange wings. Of course, these species are important, and play a crucial role in our ecosystems but pollinators come in all forms. Some are elusive and only seen at night, like the plebeian sphinx moth while others are inadvertent in spreading pollen, like Brazil's noronha skink. Even us humans can serve as passive or active pollinators. To kick off National Pollinator Week, learn about a few of the unsung pollinators of the world and hear from our Ecologist and Collections Specialist, Dr. Rea Manderino on their importance.

Margined Soldier Beetles

Chauliognathus marginatus

Seen visiting native and non-native plants alike! Photo by Michael Carr.

Beetles can range in size from the hercules beetle to smaller species, like Chauliognathus. Soldier beetles are slender, with colored black and orange-ish brown hardened wings. Fireflies are a close relative, with similar physical characteristics and similar distributions throughout central and eastern US. Another characteristic of all beetles is their chewing mouthparts which set them apart from something like a butterfly, which has a coiled proboscis to consume nectar.

In their early life stage, female soldier beetles place their eggs in moist soil layers or in the leaf litter of meadows, lawns, and forests. Our Ecologist and Collections Specialist Dr. Rea Manderino shares that the larvae like to consume caterpillars. As the larvae grow they turn into predators and feed on the eggs of other insects like stink bugs, and consume other garden pests like aphids and thrips.

Despite their perhaps unsavory dining habits as larvae, adult soldier beetles are excellent pollinators. When it comes to flowers, they’re non-discriminate travelers which means they move from plant to plant carrying with them an abundance of pollen they picked up along the way.

Bats

Bats get a bad wrap. Often they’re only brought out into the spotlight during the month of October or get misrepresented in Hollywood movies. In fact, if you enjoy bananas in your smoothies, or kicking back with a margarita, you should take a moment to thank a bat. Nearly 530 species of neotropical plants are either fully or partially dependent on bats for pollination, including bananas (Musa sp.) and agave (Agave sp.).

Bats make great pollinators for a number of reasons. As activity for the daylight pollinators dwindles down, bats are just starting their day. Guided by a musty, fetid scent, they travel to the night blooming flowers of the deserts and tropical regions collecting pollen on their faces and bodies. One benefit from this is that bats are able to pick up larger amounts of pollen and larger sized pollen grains than your average insect. Not only that, but because of their bigger bodies and wings, they can travel farther and thus carry pollen longer distances. This becomes crucial as the landscape of tropical rainforests continues to be fragmented, bats step up to the plate and help maintain the genetic continuum of these fragile species, which means not only are they pollinators, but conservationists too.

Blue-winged Scoliid Wasp

Scolia dubia

The wasps are another misunderstood pollinator species. Often all wasps get lumped in with the introduced social wasps, despite being just a small fraction of the Hymenoptera order. The blue-winged scoliid wasp is a native of North America and they’re often found on several of our native herbaceous perennials like mountain-mint (Pycnanthemum muticum), goldenrod (Solidago sp.), and Northern rattlesnake-master (Eryngium yuccifolium var. yuccifolium).

True to their name, their wings have a stunning blue iridescence. Photo by Michele Hamilton.

The blue-winged wasp, like soldier beetles, has four stages to their life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. What’s different though is where the first stage begins. As the female searches for a place to lay her eggs, she flies close to the soil. Then, as Rea shares, the females “burrow into the ground to find larvae of scarab beetles to lay their eggs in.” This is done specifically by stinging, which paralyzes the beetle grub and alludes to another common name for this species, grub hunter.

Other Small Mammals

Not just for the birds and the bees, pollination can be facilitated by a variety of other smaller mammals. Broadly speaking, flowers that get pollinated by small mammals are open at night, have a wider flower shape, and, as we learned with bat-pollinated flowers, have a musty fetid odor. Usually it’s a combination of these factors (and more) that result in pollination, but with some flowers, scent is king.

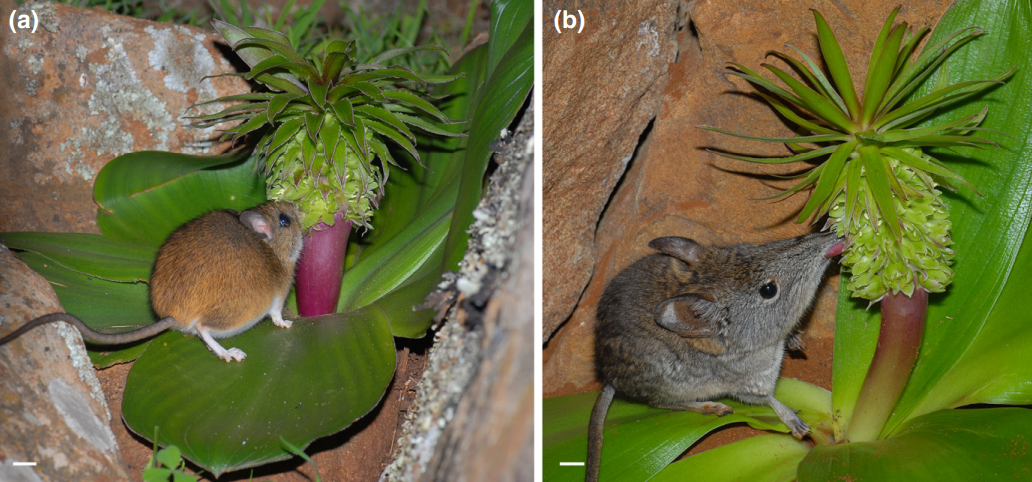

Growing in the landscape of South Africa’s Cape Floral Region is the pineapple lily (Eucomis regia). This member of the asparagus family (Asparagaceae) produces a tall axis of small, nondescript flowers. The scent of the flowers to a human nose is likened to a boiled potato, but to the Namaqua rock rat (Micaelamys namaquensis), it’s an attractive smell. The scent alone is enough to cue these small desert rodents to the plant, where pollen grains are then left on their head and fur.

One study in 2019 directly demonstrated that this species of pineapple lily relies on visitation from the Namaqua rock rat and other smaller mammals to produce seeds. This, like with bats, demonstrates the invaluable role non-insect pollinators have and the importance of supporting and conserving their habitats.

If you are interested in learning more about the diversity of insects and how to support them, sign up for one of our half-day or daylong workshops led by our Biodiversity Conservation Team!

Thank you to Ecologist and Collections Specialist Dr. Rea Manderino for her time and insights into this blog post. Banner image taken by Dr. Michele Sanchez.

References:

Baker, J. (2019, September 11). Blue-winged Wasp. Blue-winged Wasp | NC State Extension Publications. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/blue-winged-wasp

Bat Conservation Trust. (n.d.). Bats as pollinators - why bats matter. Bat Conservation Trust. https://www.bats.org.uk/about-bats/why-bats-matter/bats-as-pollinators#:~:text=The%20pollination%20of%20plants%20by,at%20the%20bottom%20of%20them

Bat Pollination. US Forest Service. (n.d.). https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/wildflowers/pollinators/who-are-the-pollinators/bats

Bessin, R. (2018, September 4). Scolia dubia swarming lawns. Kentucky Pest News. https://kentuckypestnews.wordpress.com/2018/09/04/scolia-dubia-swarming-lawns/

Cox, S. (2011, July 5). Margined Leatherwing. MOBugs. https://mobugs.blogspot.com/2011/07/margined-leatherwing.html

Fleming, Theodore H., et al. “The Evolution of Bat Pollination: A Phylogenetic Perspective.” Annals of Botany, vol. 104, no. 6, 2009, pp. 1017–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43576383.

Newton, B. (2006). Solider Beetles of Kentucky. Kentucky Critter Files. http://www.uky.edu/Ag/CritterFiles/casefile/insects/beetles/soldier/soldier.htm

Wester, Petra, et al. “Scent Chemistry Is Key in the Evolutionary Transition between Insect and Mammal Pollination in African Pineapple Lilies.” The New Phytologist, vol. 222, no. 3, 2019, pp. 1624–37. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26675913.