Mary Vaux Walcott: A Bouquet of Talent

OSGF

Mary Vaux Walcott (1860-1940). Image via the Smithsonian Archives

Born on this day in 1860, Mary Vaux Walcott was a botanist, glaciologist, and outdoorswoman who created close to 1,000 botanical sketches and illustrations in her lifetime. The Smithsonian published nearly 400 of her illustrations, all of which were done in the rugged landscape of the Canadian Alps, sometimes devoting upwards of 17 hours in the field recording every detail, every change in light of each plant. Read on to learn about the breadth of her pursuits and how her love of the outdoors shaped her life.

“My First Painting” done by Mary in 1868 via the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Born in Philadelphia to an affluent Quaker family, Mary received a true Victorian upbringing, attending a private school which prioritized subjects like math, science, astronomy, and geography. She also traveled frequently as a child with her family. Influenced by the interests of her mother, Sarah Morris, Mary was gifted a set of watercolors which she used to paint landscapes and flowers. Tragedy struck the Morris family in 1880 with the passing of her mother. Even though Quaker ideology viewed women as equals, Mary was expected to attend to the household duties upon her mother’s death. This however didn't mean that she had to relinquish her interests entirely. In fact, Mary and her family were active in the Photographic Society of Philadelphia and she attended the Academy of Natural Sciences.

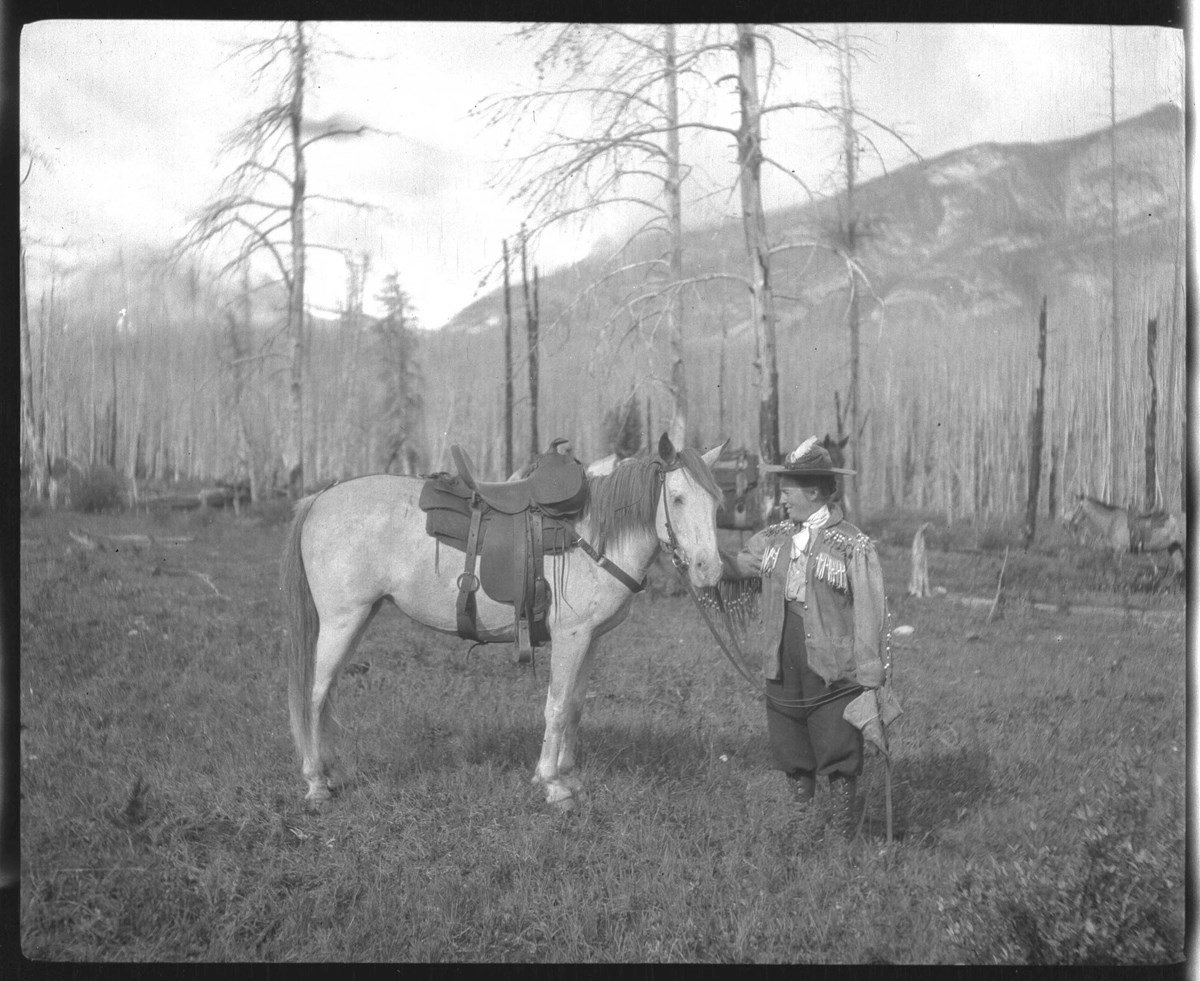

Mary Vaux at Illecillewaet Glacier, 1898. Vaux family fond, (v653-ng-456) via the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

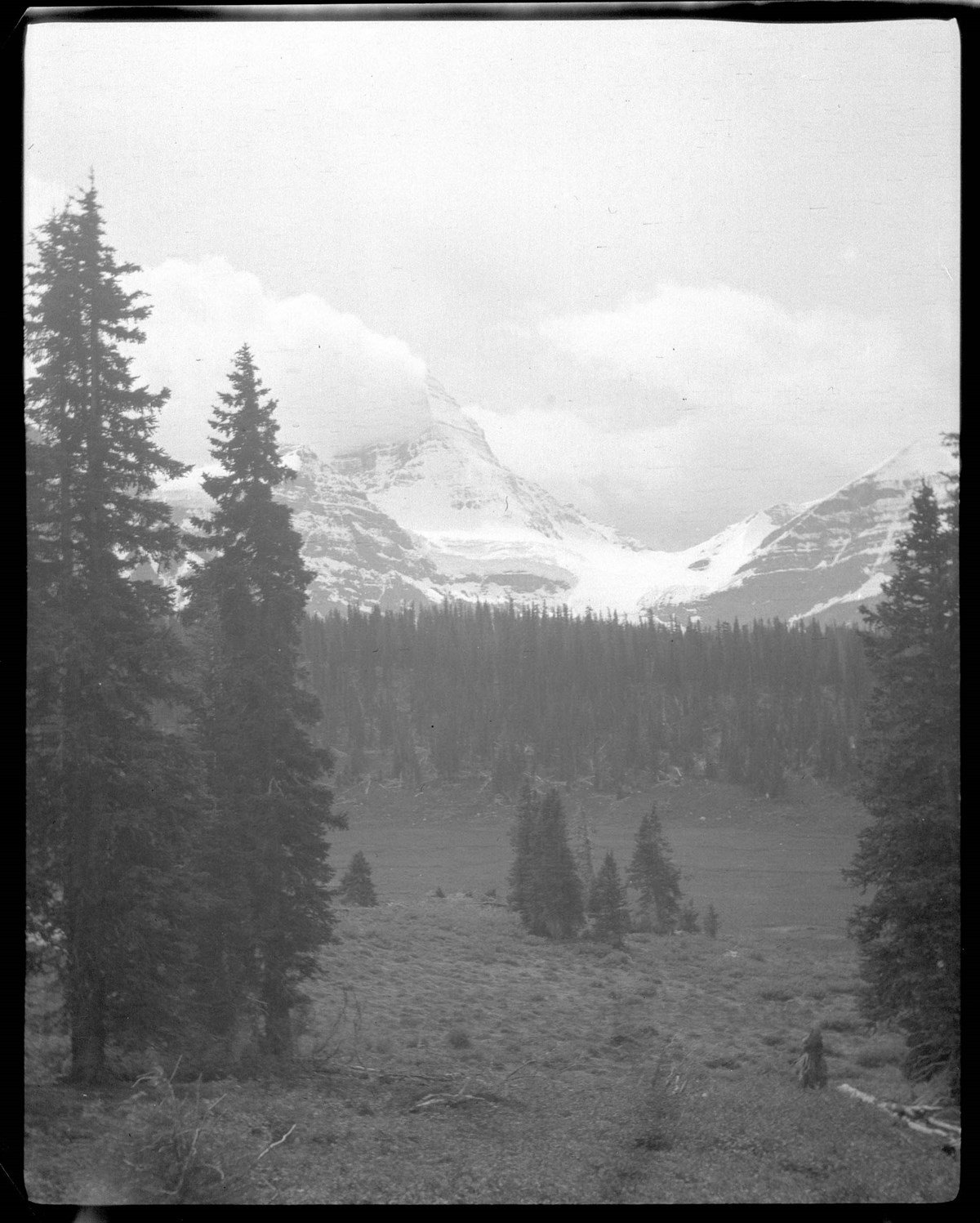

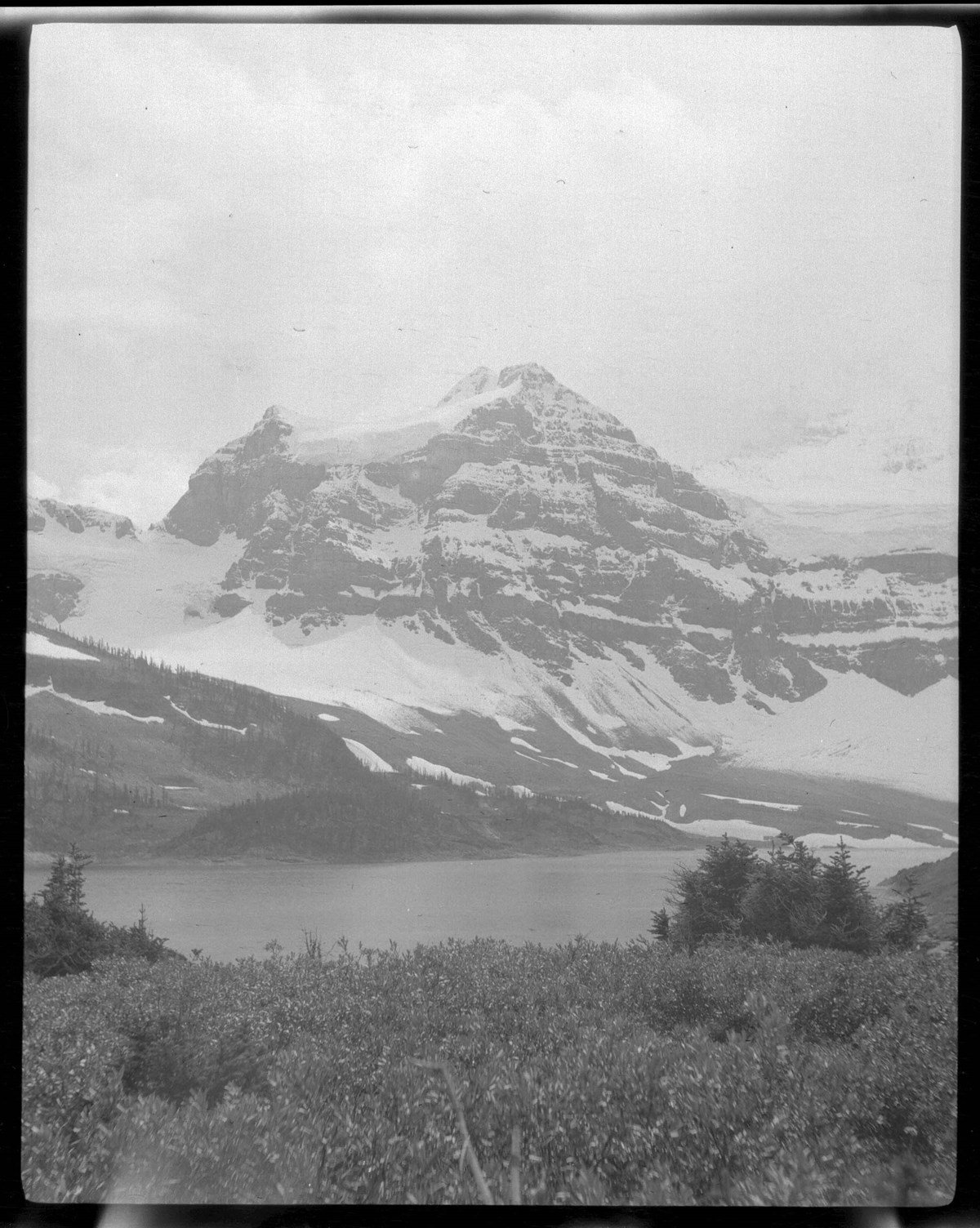

As the family put their travels on hold for a period of mourning, the Canadian Pacific Railway was being completed and offered its second transcontinental service just in time for the Morris family to utilize it again. Not yet even in her 30s Mary, along with her father and two brothers, went on a 10,000 mile long trek to the American West and Canada. It was on their return visit that she was first exposed to the pacific wilderness and grandeur of the Canadian Alps. They made a stop at the recently constructed Glacier House in what is now Glacier National Park, sited on the historic lands of the Nehiyawak and Métis Nations. At this first visit, Mary and her brother took photos of the nearby Illecillewaet Glacier, which some argue is the first formal documentation of this glacier.

“The ice was about 75 ft thick, & a quarter of a mile across the foot, & extended up the mountain several miles. Here & there were great seams & cracks in which the ice was the most lovely deep blue green color, while still higher up it was very rough on the surface, the whole having a grayish white appearance.”

Her family subsequently returned to that same spot years later and observed that the glacier had receded significantly in the time that lapsed. Wanting to understand this phenomenon and even then recognizing the significance of the glacial recession, they began making annual trips to the area. During these visits Mary and her younger brother William not only photographed but also surveyed and measured the glacial retreat at the same spot. All of these early recordings are regarded as foundational and help to paint an early picture of a changing climate.

The two also became skilled landscape photographers. As a Photographic Society of Philadelphia member, Mary was adept in the photo development process, creating makeshift darkrooms at campsites or hotels. This was a feat in and of itself as at that time, photography was more involved than a simple ‘point and shoot’ approach and involved heavy equipment and delicate glass slides. Back home, she would often make lantern slide presentations to friends and community members. To create these presentations, a photograph print was set onto a glass slide and was meticulously colored by hand with a small paintbrush.

Between the years 1897 to 1912, the siblings took over 2,500 pictures of the Canadian alpine region. Even after the passing of her youngest brother, William, Mary still continued to make trips to the Canadian Rockies independently.

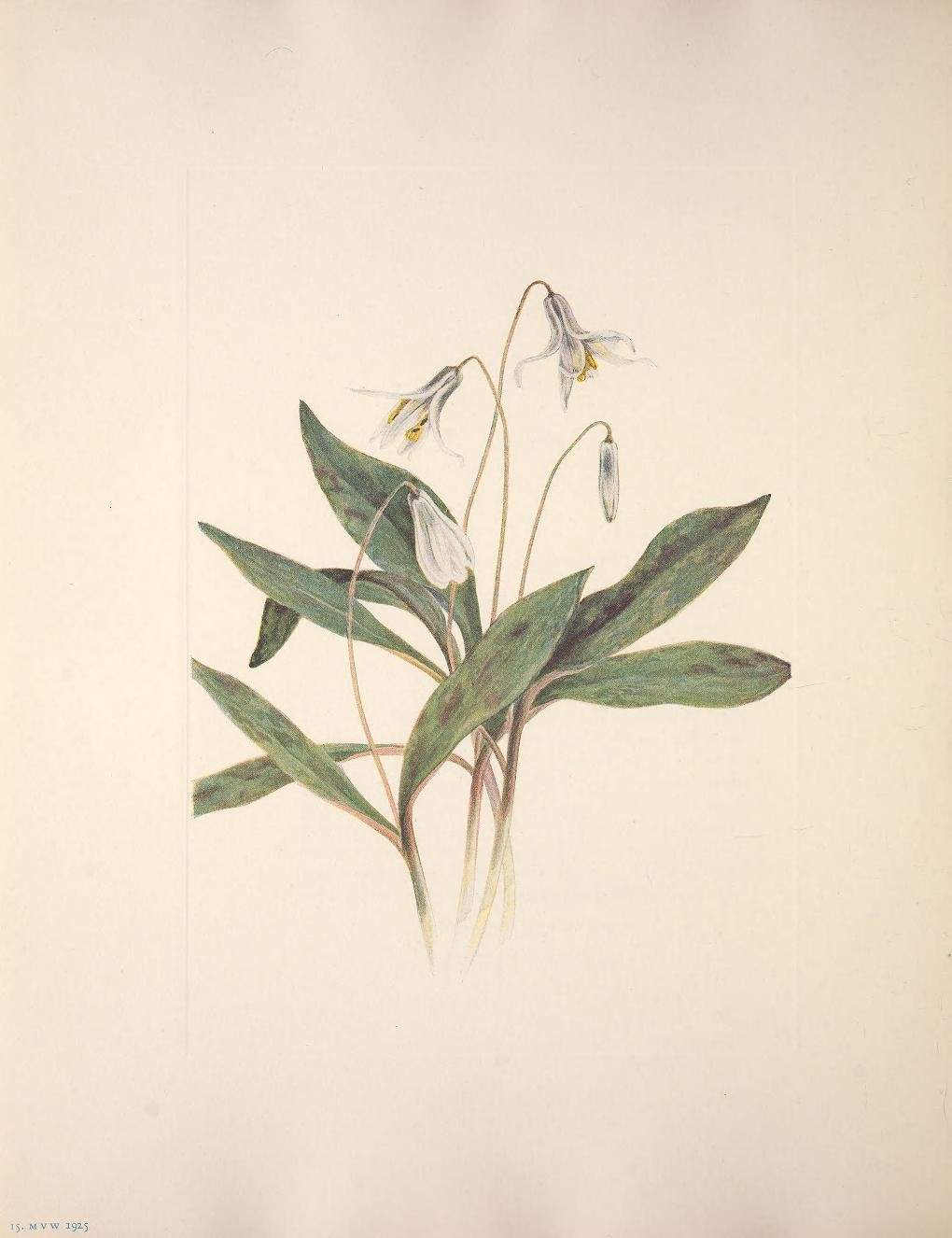

During these frequent trips she was approached by a botanist visiting the Glacier House to paint a small member of the daisy family, Arnica sp. which pointed Mary in the direction of botanical illustration. Throughout the following years she searched for species to paint– it’s even said that she would spend up to 17 hours of observation, noting the changes in petal color or leaf in different stages of natural light.

Botany wasn’t her only focus. As Mary traversed the rocky landscapes, it only makes sense that her orienteering and skills as an outdoorswoman became sharpened too. Ten days before her 40th birthday, in 1900, she summited St. Stephens making her the first woman of European descent to climb the mountain. Her childhood friend and fellow botanical artist Mary Schaffer later called for a mountain in Jasper National Park to be named in her honor.

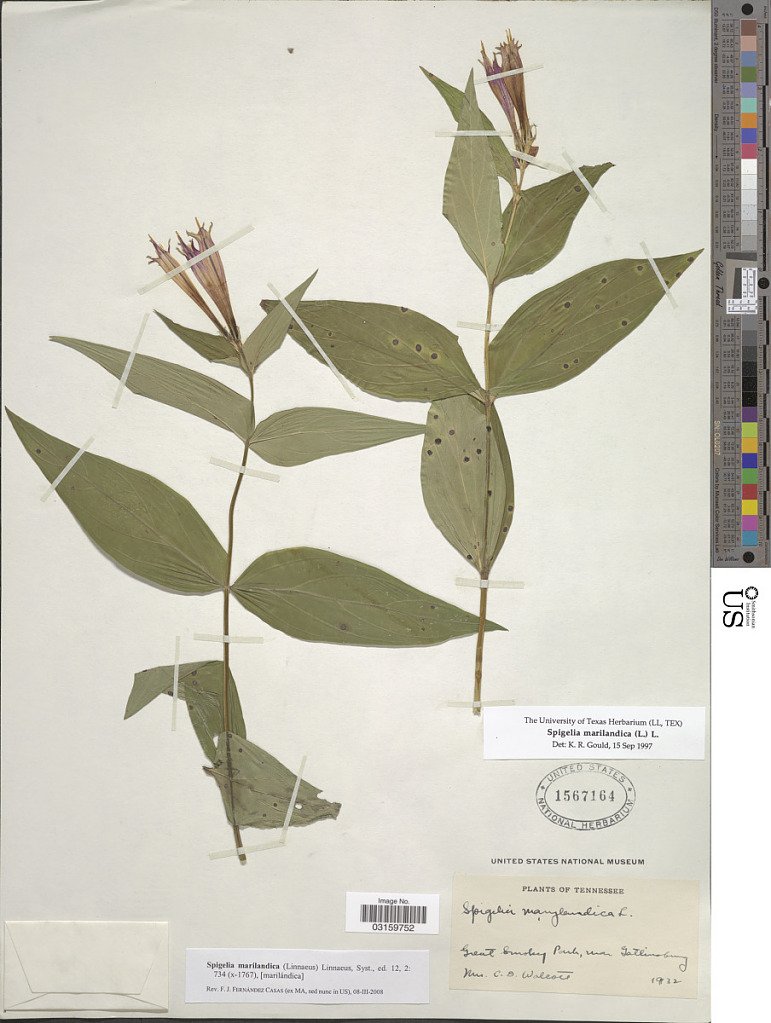

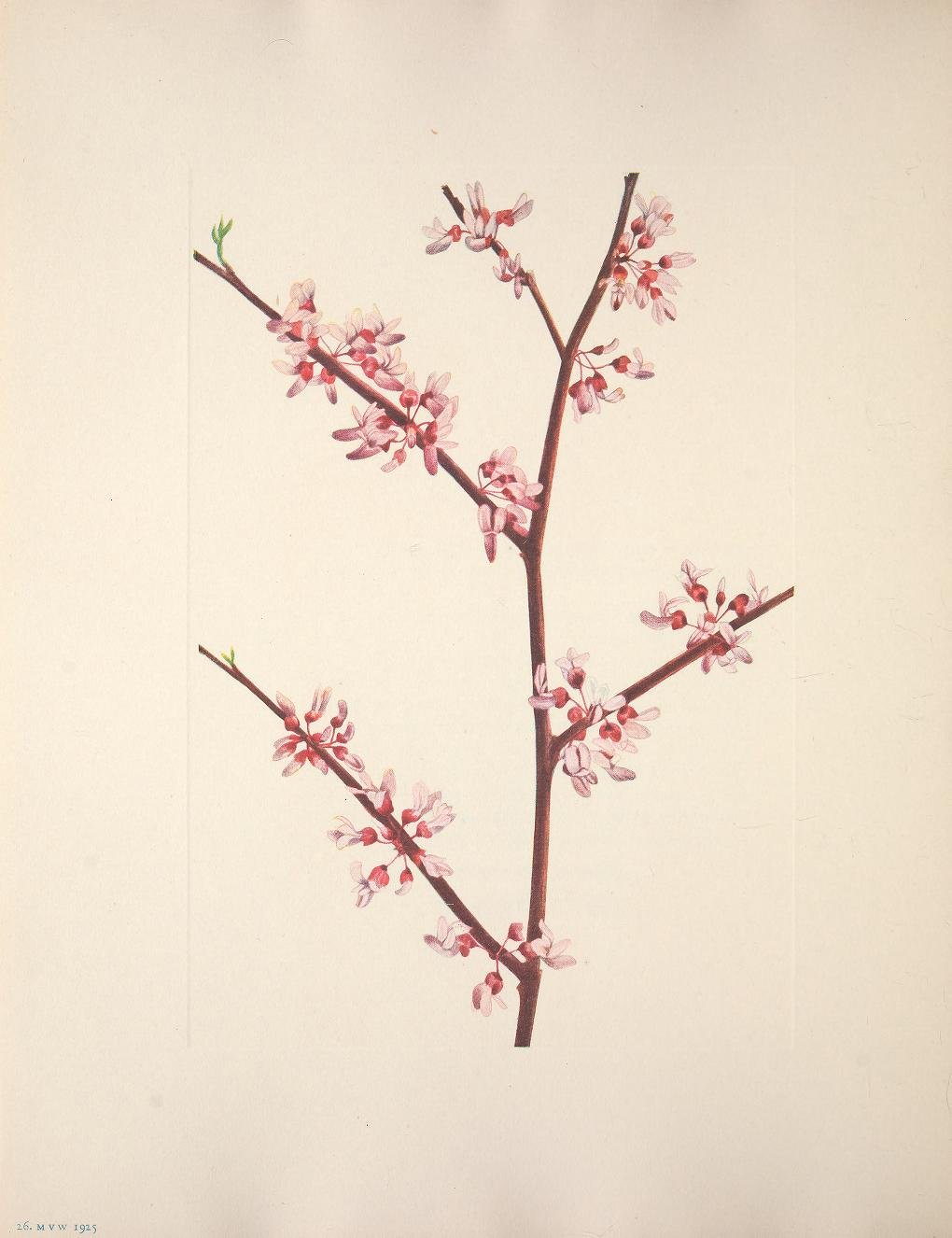

This specimen was taken from the grounds of the White House and shared with Mary by Mrs. Coolidge, former First Lady of the United States who was a close friend of Mary.

Through pursuit of her passions, she met Charles Doolittle Walcott, a paleontologist and secretary for the Smithsonian Institution, and his then wife Helen. The couple were in the early stages of excavation of the Burgess Shale, which contains fossils over half a billion years old. Following Helen’s tragic death in a railroad accident, the two married years later in 1914. They took up residence during the winter months in Washington DC, and Mary assisted with the cataloging, sketching, and photography of the shale fossils.

The laundry list of Mary’s accomplishments is long. Her biggest and perhaps most underlined work, North American Wild Flowers, was produced by the Smithsonian in 1925. At the request of fellow botanists and scientists, she created an impressive five volume work with nearly 400 botanical illustrations of species she observed from her years of study and travel and is considered to be the “Audubon of Botany''. Not only that, but Mary is the recorded collector for 470 specimens housed in the Smithsonian herbarium, roughly half of which are paleobiological specimens. The other half are pressed plants, many of which are illustrated in her volumes. Her botanical illustration style is formative for the late 19th century; as mentioned earlier, all of her works were produced in the field, not from pictures like some of her other contemporaries.

References:

H. W. Y. “Mary Vaux Walcott.” Science, vol. 92, no. 2391, 1940, pp. 372–73. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1667069.

Rudolph, Emanuel D. “Women Who Studied Plants in the Pre-Twentieth Century United States and Canada.” Taxon, vol. 39, no. 2, 1990, pp. 151–205. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1223016.

Jones, Marjorie G. “Bowling Along: Early Travel Adventures of Mary Morris Vaux.” Quaker History, vol. 100, no. 1, 2011, pp. 22–39. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41947704.

YouTube. (2022). Mary Vaux Walcott: A Life in Bloom. YouTube. Retrieved July, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XGDdROmQarM.