The Secret Cliques of Plants and Pollinators

OSGF

As habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change threaten insects, birds, and bats, many people are learning that growing native plants can help protect local pollinators. Native pollinator gardens are an amazing way to provide food sources and habitat for these essential animals. But did you know that not every plant attracts or feeds the same pollinators? Read on to learn how plants appeal to specific groups of pollinators and how you can use this knowledge to plant a thriving pollinator garden.

THE PATH TO POLLINATION

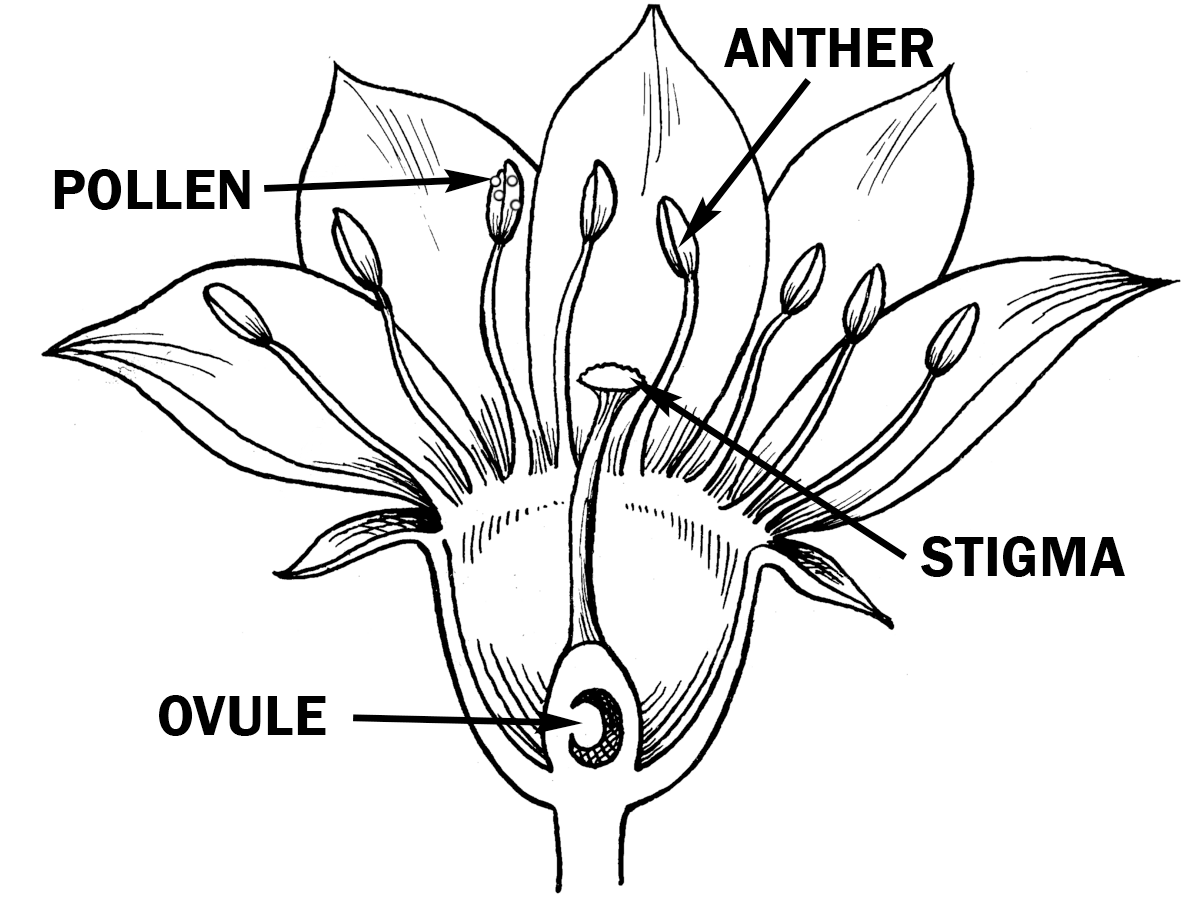

Pollination is one of the ways plants are able to reproduce. Through their flowers, plants are able to exchange genetic information and produce seeds. To understand pollination, it helps to know a little bit about the anatomy of a flower.

Pollen or pollen grains are packets of genetic material that can travel between plants.

Ovules are packets of genetic material that stay put on a plant inside its flowers. Ovules will become seeds if properly fertilized by pollen.

Anthers are the structures that produce pollen.

Stigmas receive pollen and help the information in a pollen grain reach an ovule.

Put simply, pollination is when a pollen grain moves from an anther to a stigma.

POLLINATION STRATEGIES

There are a lot of ways for pollen to move from the anther to a stigma of the same species. Some plants, including most grasses and a lot of trees like oaks, maples, and hickories, have their pollen carried on the wind. Others have flowers shaped in such a way that allows pollen to be transferred onto the stigma of the same flower in a process known as self-pollination. Countless other species rely on animals to carry pollen from one flower to another. These animals are known as pollinators.

Black Willow trees (Salix nigra) trees are wind pollinated

Plants that rely on wind for pollination must produce large quantities of pollen to ensure success. These species are largely responsible for the sneezing and runny noses common during the spring allergy season. In contrast, plants that have evolved with animal pollinators benefit from a more targeted approach to pollen transfer. There’s no need to waste resources making large amounts of pollen if it can be hand-delivered.

However, pollinators don’t visit flowers to help out the plants; they are focused on their own survival and reproduction, so plants have evolved flowers that entice, reward, or trick the pollinators they depend on. For many pollinator species, the pollen itself is the reward; pollen is high in protein and an important food source for bees and some flies, birds, and bats. Some flowers produce nectar, a sugary liquid reward for animal visitors, while others have scents or oils that pollinators harvest. Still others attract pollinators through deception– producing the smell of decaying flesh to lure in carrion flies and beetles.

ATTRACTING ANIMALS

Some plants are popular with many different kinds of pollinators and can be considered generalists, like bee balms (Monarda spp.), while others are specialists and have adapted to attract specific groups. It is thought that this specialization improves the rate at which successful pollination occurs because pollinators are more likely to visit another flower of the same species if they are being advertised to specifically. Floral signals vary between pollinator groups depending on the animals’ sensory abilities, but scent and color are the primary attractants that flowers use to capture pollinators’ attention.

The shape, structure, and size of a flower must allow pollinators to contact the anthers and stigma of the flower for pollination to be successful by a given animal. Because different groups of pollinators have different physical shapes (bees and hummingbirds, for example, are vastly different in size) and sensory limitations (bees and birds vary in how they see and smell), flowers that attract the same group of pollinators tend to share many characteristics. We call a group of these qualities a pollinator syndrome. Though many people are most familiar with the word ‘syndrome’ in a medical context, it also refers to ‘a set of concurrent things…that usually form an identifiable pattern’ (Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary). Once you know what to look for, you may start to see pollinator syndromes everywhere, and they can help you to select the best plants for a pollinator garden.

BEES

There are too many pollinator syndromes to cover each one in detail here, but we’ll go over a few, starting with bees. Bees are one of the first pollinators to come to mind for most people, and the eastern United States is home to around 770 species of bees. Bee vision doesn’t include the color red, but they can see ultraviolet, or UV, light. This is why flowers primarily pollinated by bees tend to be bright white, yellow, or blue, but not usually red. Their UV vision is why bee pollinated flowers may utilize UV patterns called nectar guides. Although we can’t see them, these patterns—visible to bees (and butterflies)—help point the bees directly to where nectar is located in the flower.

Bees really appreciate an easy landing, so they like to visit flowers with either a wide lip to use as a landing pad, like Great blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica), or are wide and open, like Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis). Nectar is present in some bee-pollinated flowers as a reward and source of carbohydrates for their pollinators, but bees collect pollen as food for themselves and their offspring. Therefore not every bee-pollinated flower needs nectar to ensure a return visit.

BUTTERFLIES

Another popular pollinator group is the butterflies and moths. There are distinctions between the pollinator syndromes of butterflies and moths, but they share several similarities. Because both butterflies and moths feed using a long mouthpart called a proboscis, flowers hoping to attract either pollinator tend to have deeply hidden nectar and may even place it at the end of a long tubular flower or spur, as in the case of Wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis).

As butterflies forage for food during the light of day, the flowers they visit grab their attention with the bright colors of red, pink, and orange. Many moths, however, are nocturnal and might have trouble finding flowers by vision alone, especially on moonless or cloudy nights. To counter this, moth-pollinated flowers tend to be white or other light colors to make the most of any available light and usually have a very strong, sweet smell to help lure them in. Both moths and butterflies depend on floral nectar for energy, so the flowers seeking their attention produce large amounts of nectar to encourage visits.

HUMMINGBIRDS

Another nectar-loving pollinator group is the hummingbirds. Similar to butterflies and moths, the long bills of hummingbirds mean that flowers courting their attention can hide nectar away in deep tubes or cups. The large amounts of nectar these flowers produce fuel hummingbird flight and ensure lots of visits. These flowers don’t usually have a scent because birds have very poor senses of smell. Instead, they are typically bright red or orange, colors that hummingbirds are attracted to. Some examples of flowers with the bird pollination syndrome are Coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) and Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans).

FLIES

Flowers in the above three pollination syndromes are all amazing additions to a garden for the food and nutrition they can provide for animal pollinators. But not every flower is honest with the animals it attracts. There are some species of plants that engage in deception to ensure they reproduce successfully. The pollinator syndrome that targets flies is a great example of floral deceit. Some flowers produce a foul, rotting stench to attract flies searching for dead animals or dung on which to lay their eggs. If you’ve ever been disgusted by the smell of an invasive Bradford pear tree (Pyrus calleryana) in the springtime, you’ve experienced one of the fly pollination syndromes. Fly-pollinated flowers tend to be dark purple, brown, or red, and have a rotting, yeasty, or fungal odor. Some native examples of this pollination syndrome include Skunk cabbage (Symplocarpa foetidus), Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), and North America’s largest native edible fruit, Pawpaw (Asimina triloba). Though they may not reward their pollinators with food, they’re incredibly fascinating plants that demonstrate the diversity of plant reproductive tactics.

GARDENING FOR POLLINATORS

Biodiversity is the key when it comes to supporting wildlife, and that includes pollinators. By including plants with a variety of pollination syndromes in your garden you can attract and support a high diversity of native pollinators . When planning a pollinator garden, strive to include a variety of plants that flower at different times throughout the growing season, and vary in their size, color, and shape. If there are specific pollinators you are interested in seeing more of, you can look for flowers in their pollinator syndrome to attract them to your garden. And if you can’t plant a pollinator garden, you can still support pollinators by leaving leaf litter and standing stems over the winter and reducing or eliminating pesticide use. Pollinator decline is a complex issue that won’t be solved overnight, but we can all play a part in supporting our local pollinator species and learn something new in the process.

Clouded Sulphur (Colias philodice) butterfly on Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

Thank you to our Plant Conservation Apprentice, Sam Terry, for her time and insights on this blogpost. Photos are by Sam Terry, Charlotte Lorick, and Tiffany West.

REFERENCES:

Jayne, S. F. “Make a Home for Wildlife.” Homegrown National Park. https://homegrownnationalpark.org/make-a-home-for-wildlife/. Accessed June 2025

National Research Council of the National Academies. (2006). Status of Pollinators in North America. National Academy Press.

“Pollinator Syndromes.” Pollinator Partnership, https://www.pollinator.org/pollinator.org/assets/generalFiles/Pollinator_Syndromes.pdf. Accessed June 2025.

“Pollinator Syndromes.” U.S. Forest Service, https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/pollinators/What_is_Pollination/syndromes.shtml. Accessed June 2025.

“Table 4.1: Pollinator Syndromes.” Mader, E., Spivak, M. & Evans, E. (2010). Managing Alternative Pollinators:

A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers and Conservationists. NRAES. https://www.sare.org/wp-content/uploads/Table4.1.pdf. Accessed June 2024.

Van der Kooi, C. J., Reuvers, L., Spaethe, J. (2023). Honesty, reliability, and information content of floral signals. iScience, 26(7), 107093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.107093.