Lessons in Binding from the Rare Book School

Salem Twiggs

This summer, Salem Twiggs, Oak Spring Garden Library Associate, had the opportunity to attend a course on the history of bookbinding at the University of Virginia’s Rare Book School. She shares her experience and takeaways from the course below.

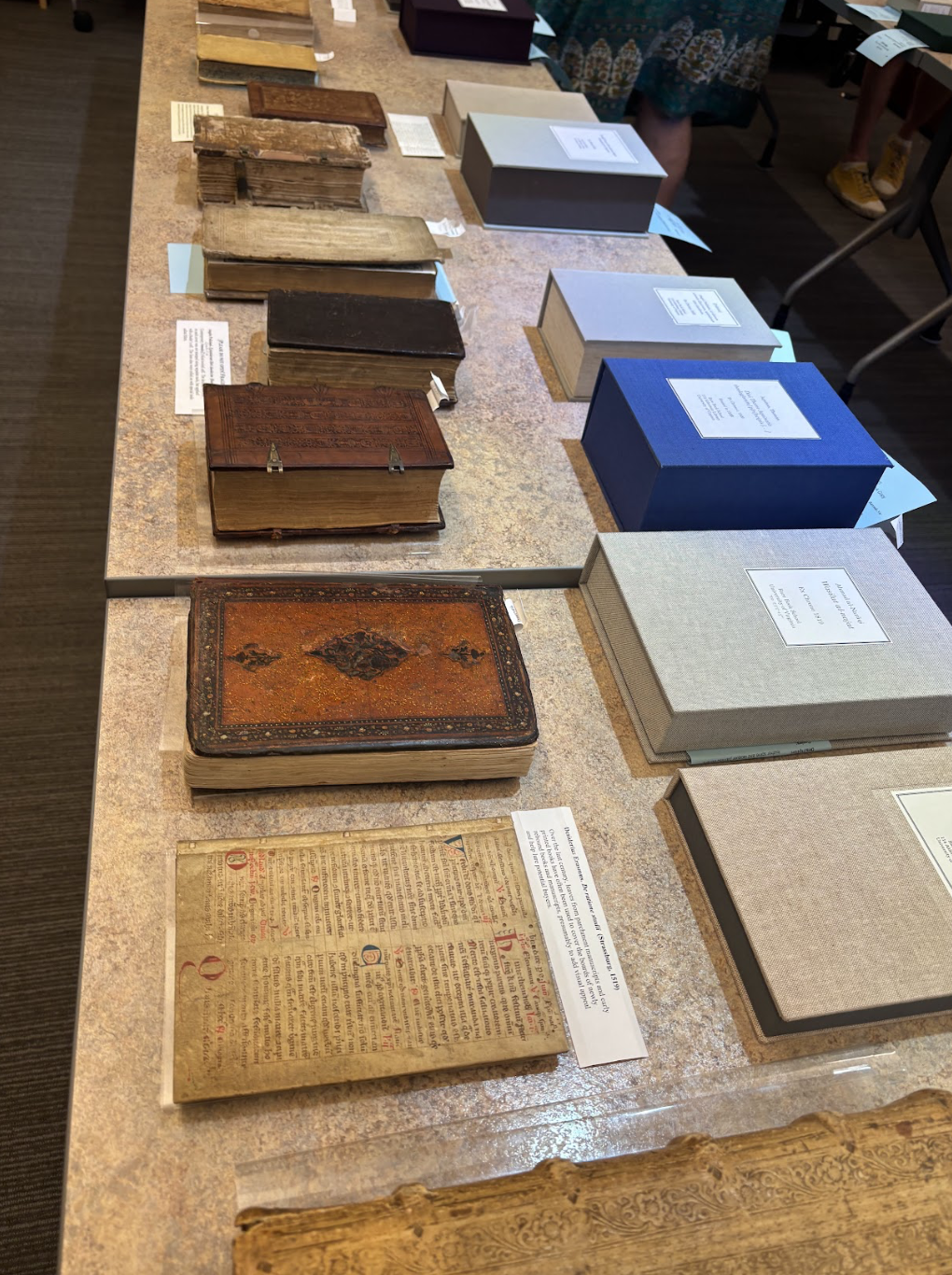

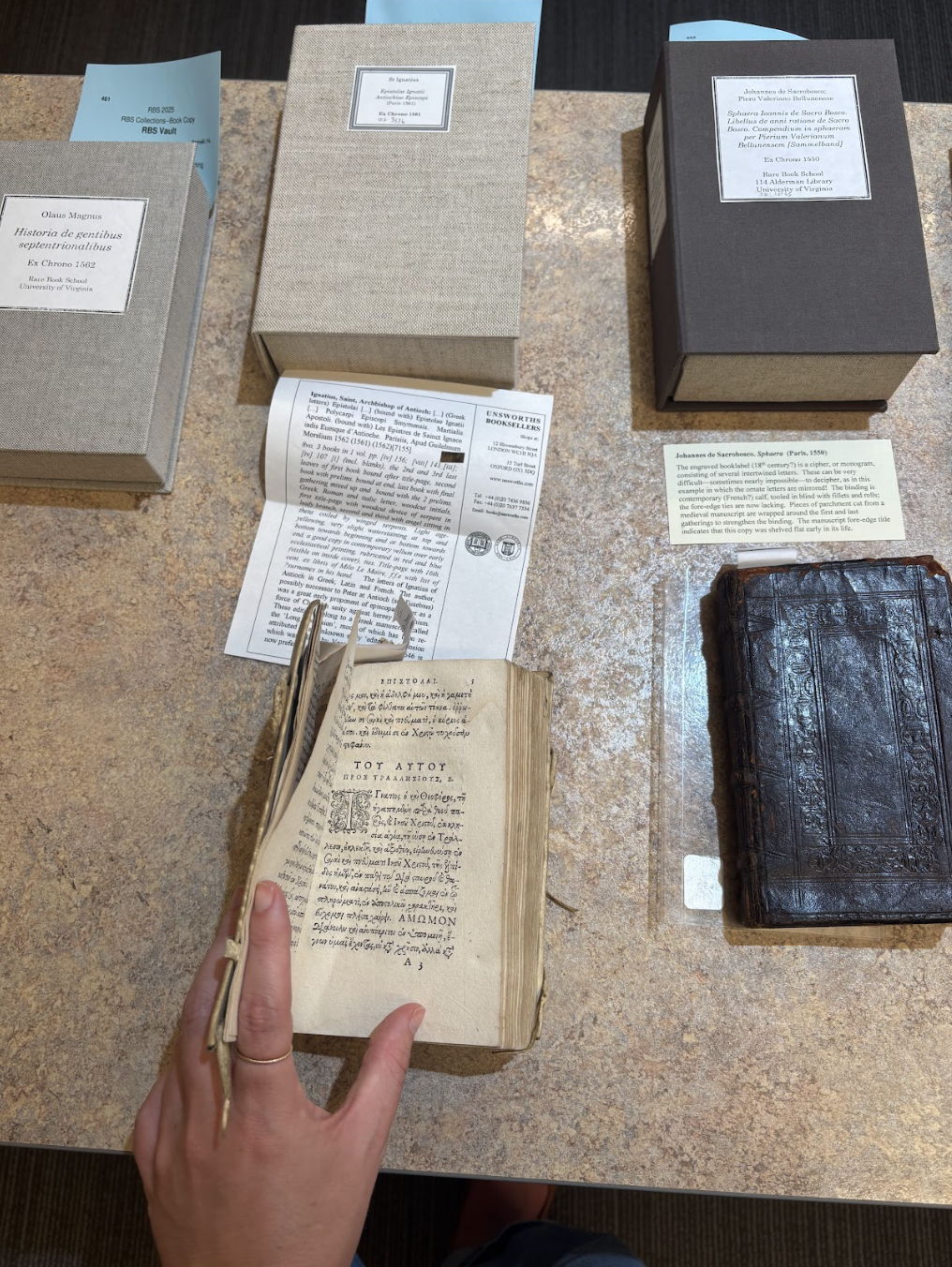

This past July, I attended Dr. Karen Limper-Herz’s course on the history of bookbinding at the University of Virginia’s Rare Book School. The Rare Book School curriculum emphasizes “reading the whole book,” which means studying the book as a physical object and not just as a means of conveying knowledge. In particular, examining a book’s binding can reveal far more about its origins or former owners than the title page alone. In the trade, the study of an object’s ownership history is known as provenance, and certain binding features offer valuable clues about a book’s past. The Rare Book School course combined lectures on the history of various binding styles with hands-on bookbinding labs and museum sessions to view examples from UVA’s extensive collection of rare books and manuscripts. Learning about bindings in this holistic way deepened my appreciation for the remarkable volumes held in the Oak Spring Garden Library.

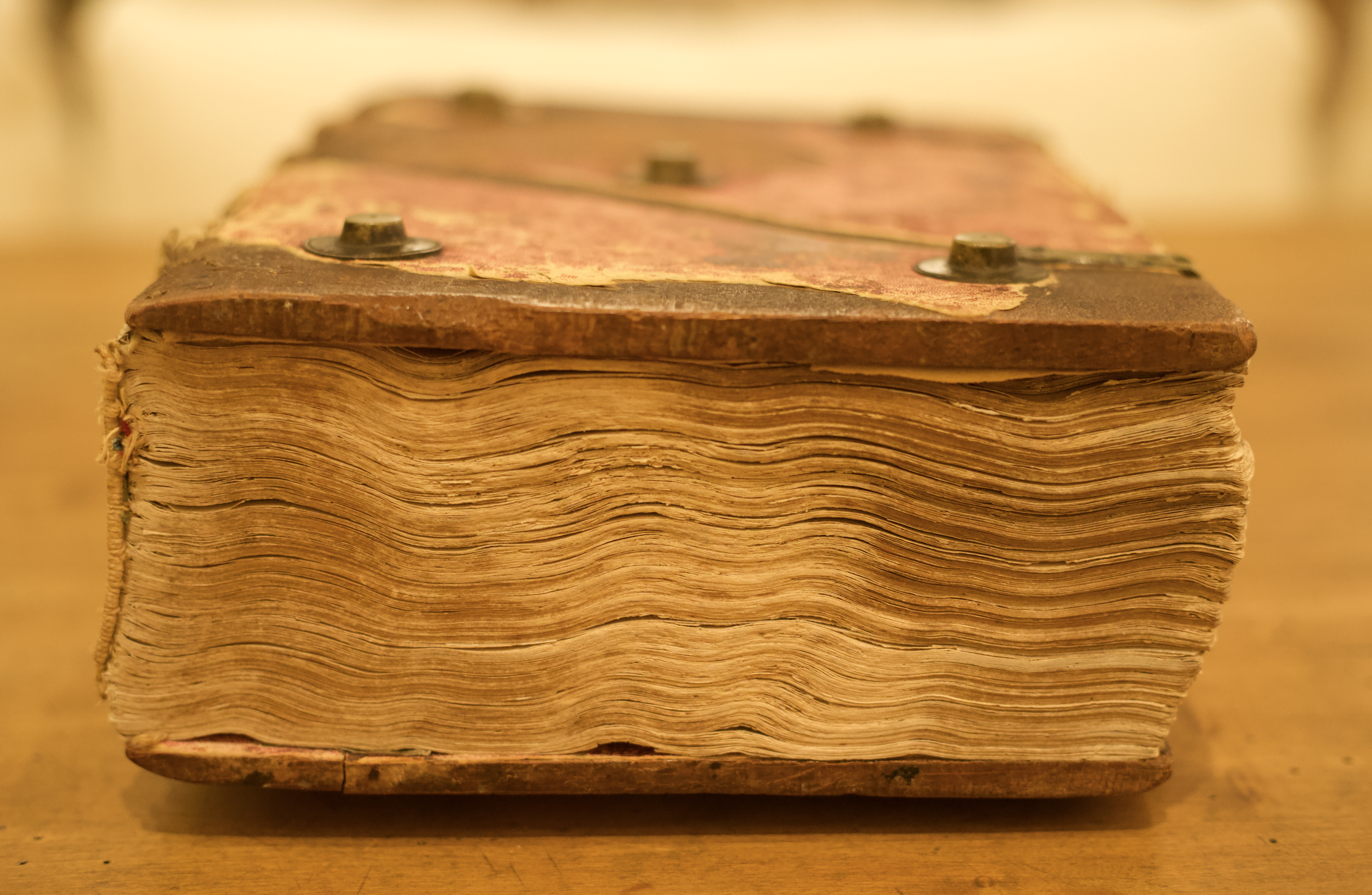

One of my favorite works in the Oak Spring Garden Library collection is a 14th-century German manuscript, Buch de Natur, attributed to Konrad von Megenberg (German, 1309–1374). A manuscript is a handwritten and typically unpublished work. Some are bound like printed books, while others remain as loose materials. This Buch de Natur is the oldest item in the library’s collection, estimated to have been written around 1350. It includes fascinating illustrations of animals and plants, including a very charming dog with the feet of a bird. Its large size and plain, heavy binding give it a striking physical presence.

14th-century German manuscript, Buch de Natur, attributed to Konrad von Megenberg (German, 1309–1374).

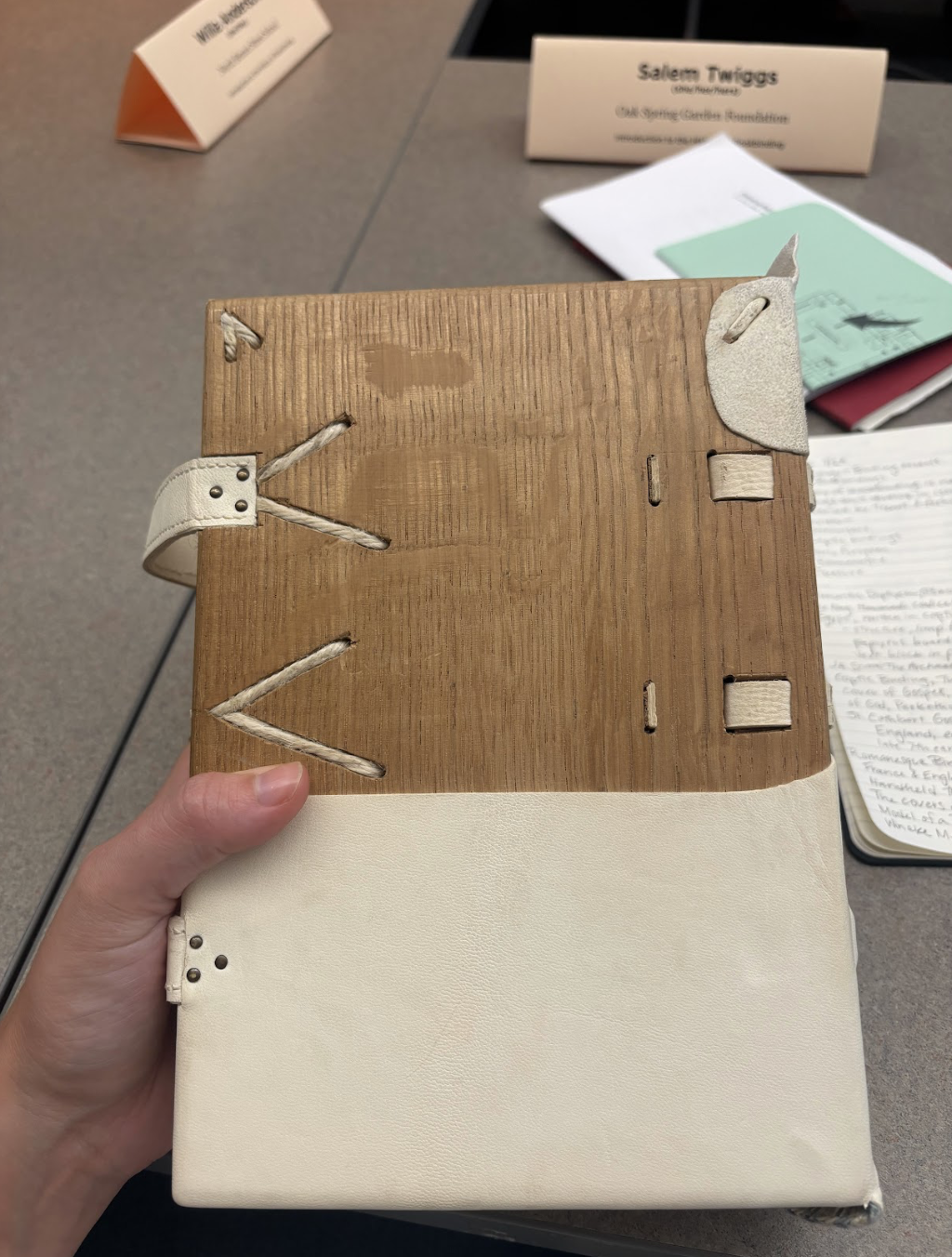

Typical of early manuscripts and early printed works, it is bound with covered wooden boards. Interestingly, although it is a German manuscript, the boards are not beveled—they are cut flush with the text block rather than angled. This absence of beveling, a common feature in early German bookbinding, may suggest an intention for later rebinding or perhaps a custom binding request by an early owner. The boards appear to be covered in deerskin, though the aging of the leather makes it difficult to identify a clear follicle pattern that would definitively indicate the animal. This leather has a pinkish red hue to it, possibly due to red dye being used on a less porous lighter color leather.

The binding also features large metal studs, known as bosses, which serve both as decoration and as protection for the boards. Books and manuscripts were sometimes fitted with clasps for added protection. On the Buch de Natur, remnants of two clasps survive on the lower cover. Clasp placement is another binding feature that can help suggest provenance: the clasps on the lower board that fasten to the upper board confirm that this is a German work of the medieval period. In contrast, English and French bindings typically place clasps on the upper board that fasten to the lower.

The spine has raised double bands with a loose weave cloth visible underneath for support. Bands are sewn supports that run across the spine. They may be raised and visible, or they may be recessed into the text block, meaning the full stack of pages that make up the body of the book, and then covered to create a smooth spine. In the Buch de Natur, the text block is level with the edges of the covered boards, which is typical of older German manuscripts

This approach became less common over time because it left the pages more exposed to damage. When the boards extend slightly beyond the pages, they form a protective buffer that helps prevent the text block from being soiled or harmed. The cover does not include decorative features or tooling. Tooling is a method in which a heated tool is pressed into the leather to create designs that are sometimes filled with gold leaf. The absence of ornamentation is consistent with other early German manuscripts. Although these features help confirm the manuscript’s origin and period, they are not distinctive enough to reveal who actually bound the work.

Taken together, the materials and construction of the Buch de Natur reveal the practical, regionally specific approach of early German binding. Its wooden boards, un-beveled edges, raised bands, plain leather, and remnants of clasps offer a clear view of the techniques and priorities of medieval craftsmen. Studying it as an object shows how much a binding can tell us about a book’s origins and history, and it provides a useful foundation for comparing the other volumes in the collection.

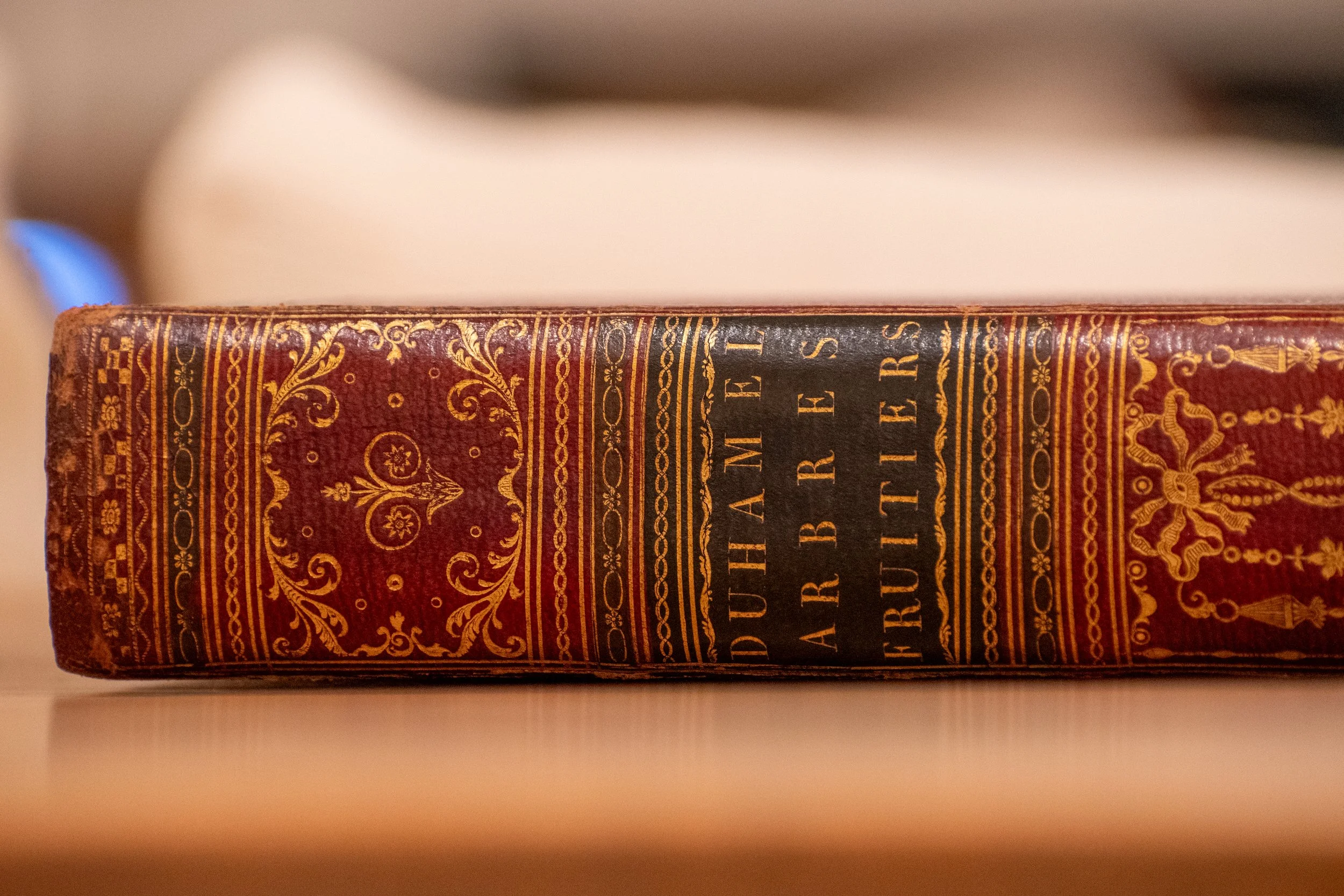

In contrast to the comparatively unadorned binding of the Buch de Natur, I have selected as a counterpoint a set of four exquisitely bound volumes from the Oak Spring Garden Library: the 1768 Traité des Arbres fruitiers by Henri Louis Duhamel du Monceau (French, 1700–1782). Whereas the binding history of the Buch de Natur has largely been lost to time, the Traité des Arbres fruitiers benefits from more substantial historical documentation. These volumes were bound by Christian Samuel Kalthoeber (fl. 1780–1817), a prominent German bookbinder active in London in the late eighteenth century. Kalthoeber, along with other German bookbinders such as Andreas Linde, relocated to England, where the bookbinding trade enjoyed a growing patronage base.

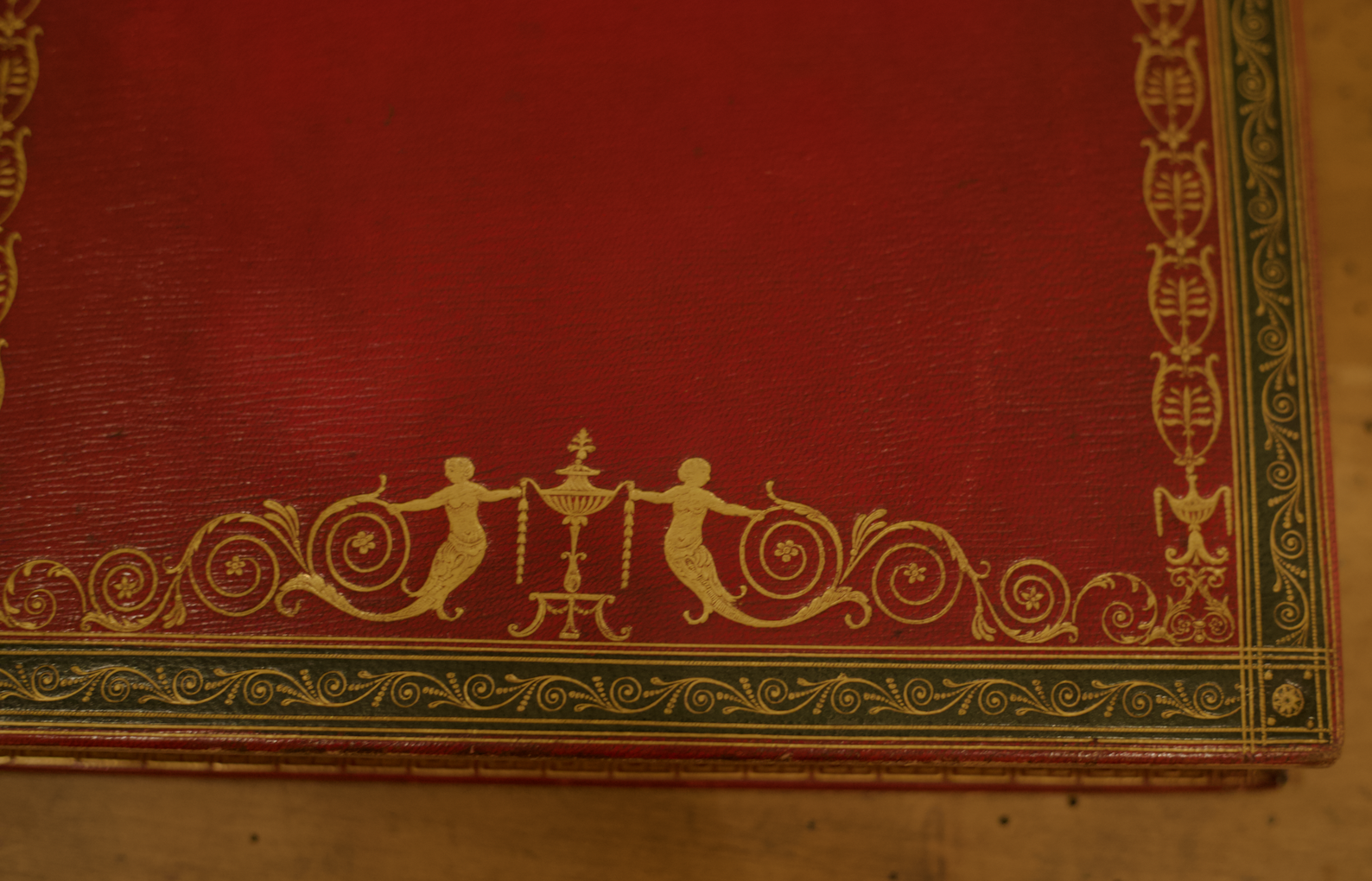

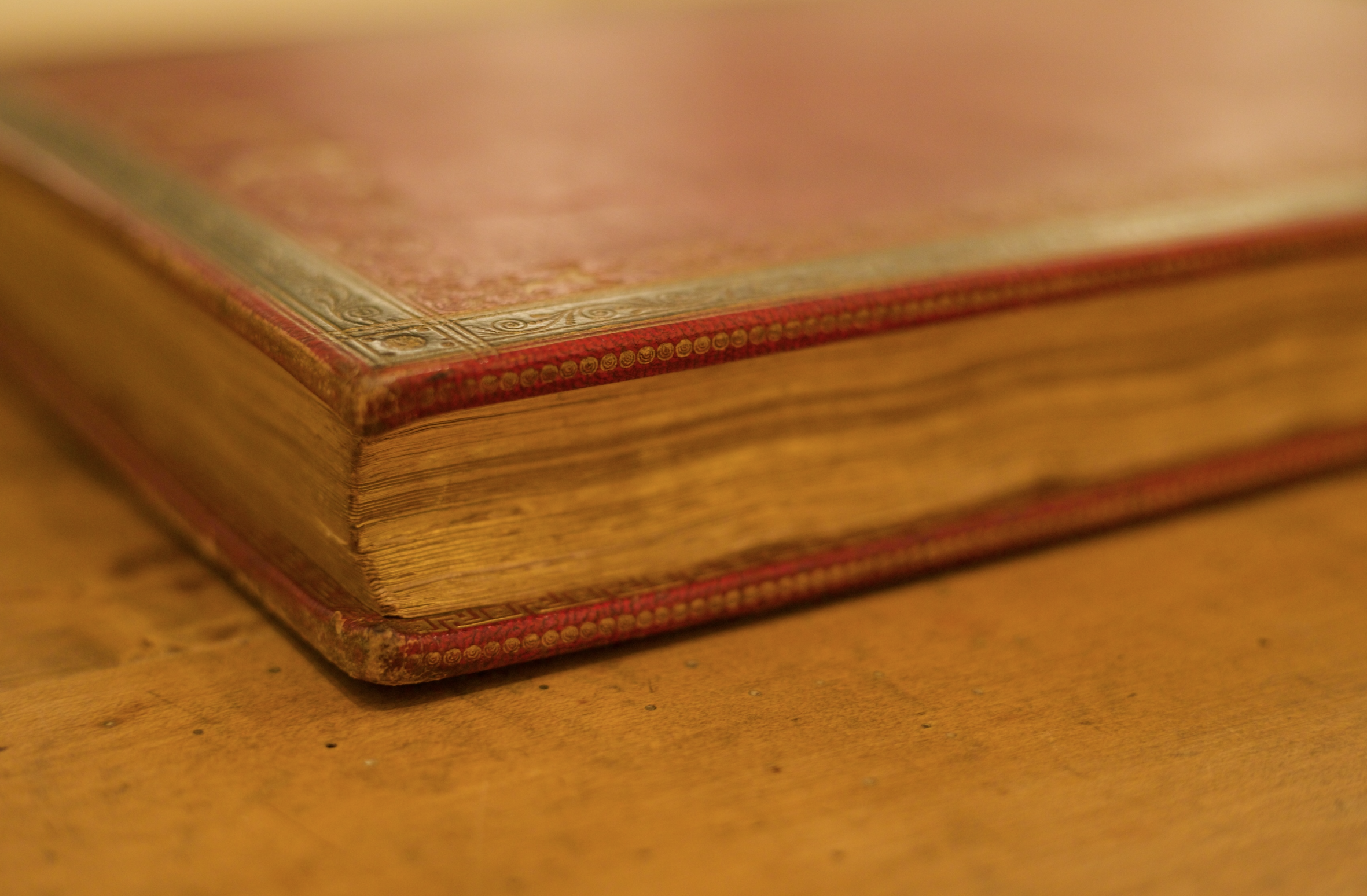

A hallmark of eighteenth-century fine bindings was the use of high-quality leathers as the principal decorative feature, with large expanses of the skin left untooled to showcase its natural texture rather than covering the surface with dense ornamentation. These volumes exemplify that aesthetic. They are bound in red calfskin over pasteboards with an undecorated central panel framed by green calfskin and enriched with gold tooling. The tooling is symmetrical and identical on both the front and back covers, and the same tools are used repeatedly to create continuous decorative patterns. Although the spine lacks raised bands, the gold tooling is arranged in horizontal stripes that visually imitate the appearance of bands. The title, volume number, and the date and place of publication are tooled on the spine on black leather labels.

As is typical of many rare books, the decoration of the binding bears little relationship to the content of the text. This treatise on fruit trees, for example, features gold-tooled mermaids and birds—motifs that do not directly correspond to its subject in natural history.

The binding also displays hallmarks of eighteenth-century English neoclassicism: the delicate tooling along the outer edges incorporates vases, palmettes, and key patterns reminiscent of the classical ornament favored during the period. It is this specific tooling design that helps attribute the volumes to Kalthoeber, as a nearly identical binding appears on a copy of William Caslon’s (English, 1692-1766) Specimen of Printing Types (1785) in King George III’s collection at the British Library, where it is identified as Kalthoeber’s work.

Studying the binding of the Traité des Arbres fruitiers offers insights not only into the aesthetic preferences of eighteenth-century English bookbinding, but also into the professional practices and networks of prominent binders like Kalthoeber. The careful selection of leathers, the arrangement and repetition of tooling, and the neoclassical motifs reveal both the technical skill of the binder and the expectations of a cultivated patronage. Moreover, comparison with documented bindings, such as Caslon’s Specimen of Printing Types, allows scholars to attribute works to specific binders with greater certainty, providing a more clear understanding of the circulation and prestige of books in this period. By examining these volumes as physical objects, we gain a richer appreciation of the interplay between craftsmanship, material culture, and the social and economic context of eighteenth-century London’s book trade.

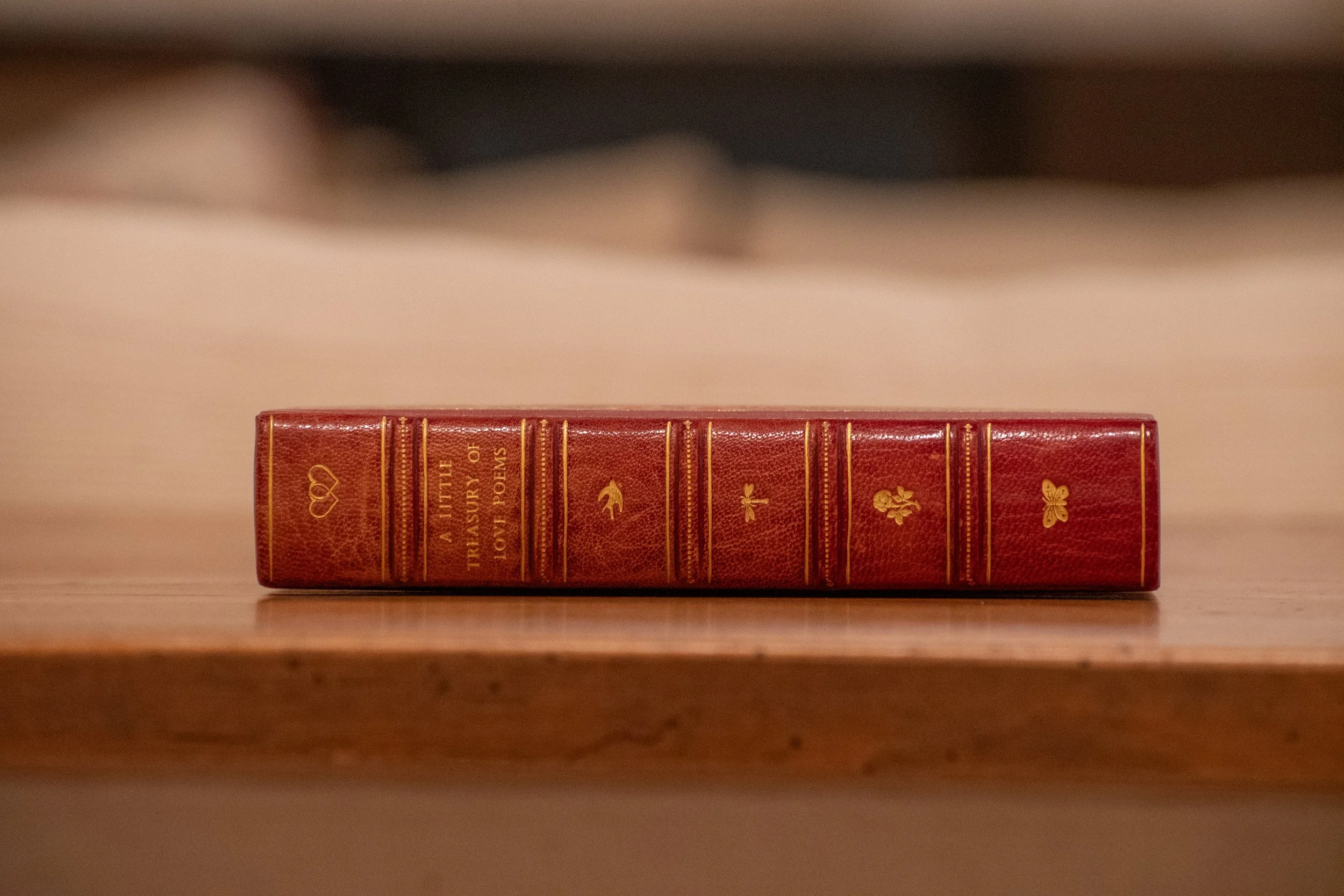

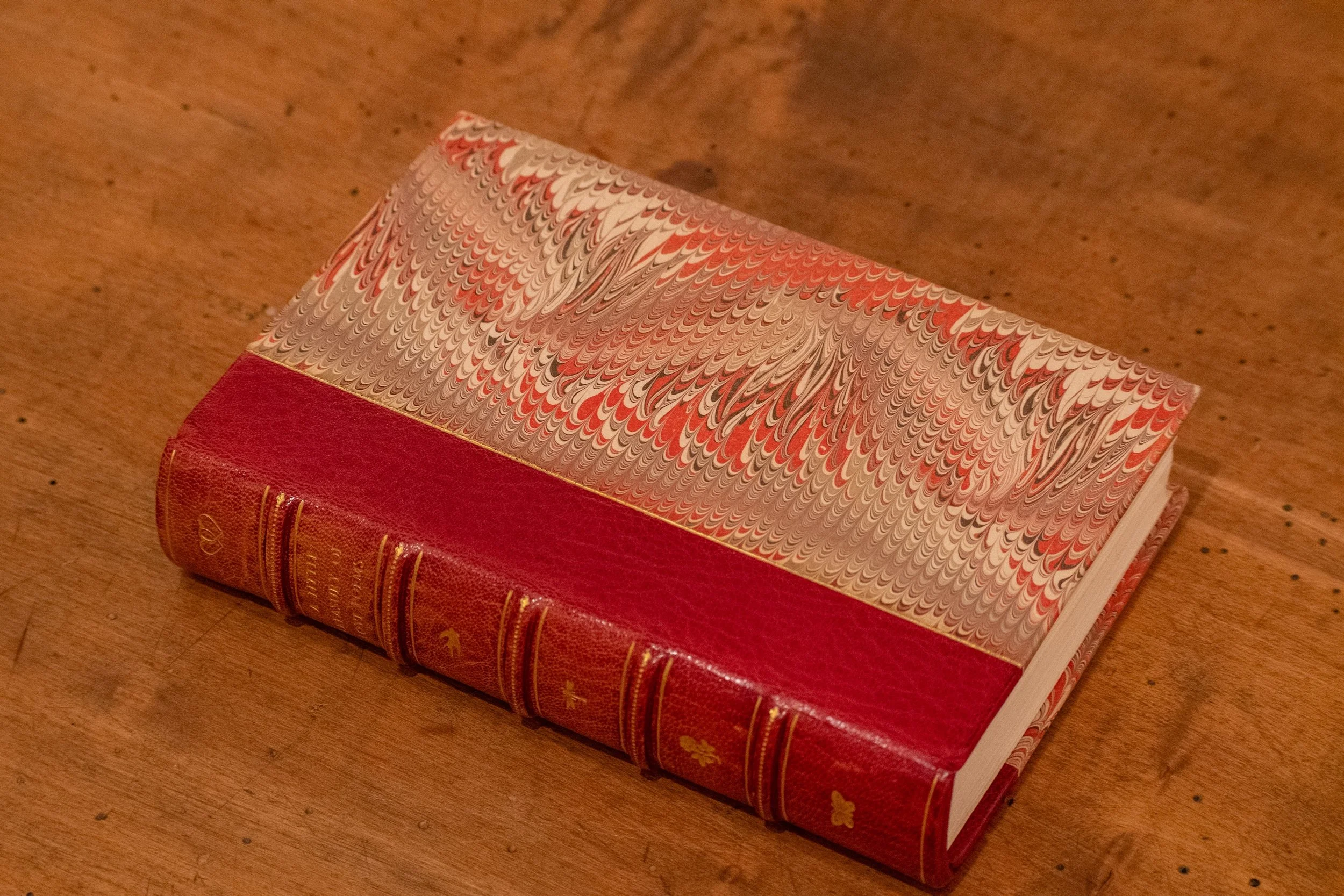

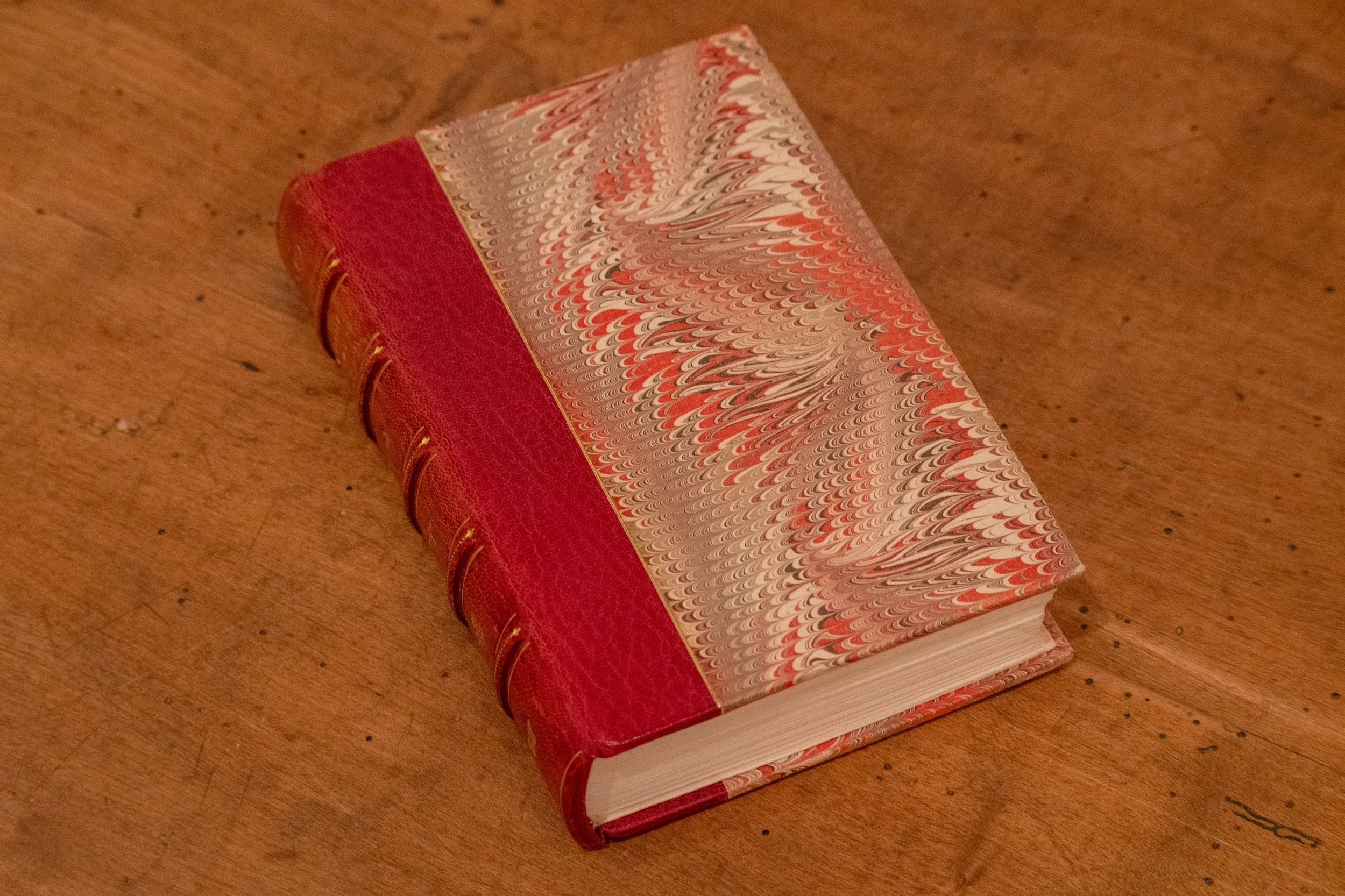

The final featured binding is contemporary, a 1950 edition of A Little Treasury of Love Poems from Chaucer to Dylan Thomas by John Holmes (American, 1904–1962). This volume was bound by Sangorski and Sutcliffe, a distinguished London-based bindery renowned in the twentieth century for its elaborate and jewelled bindings. The book is bound in quarter red morocco—a goatskin traditionally dyed with sumac to achieve a deep red hue—and is complemented by marbled paper, edged with a single line of gold tooling. The term “quarter” refers to the proportion of the cover covered in leather; in this case, the spine constitutes roughly one-quarter of the total cover area, while the remainder is covered in paper. The terms quarter, half, or three-quarter binding indicate the relative amount of leather on the combined spine and boards.

1950 edition of A Little Treasury of Love Poems from Chaucer to Dylan Thomas by John Holmes (American, 1904–1962).

Marbled paper, commonly used on both exterior covers and as endpapers, the sheets immediately following the front cover and preceding the back cover, is produced by floating inks on a viscous liquid and carefully laying the paper on the pigment. Although marbling has been practiced in multiple cultures for centuries, its use in bookbinding originated in Persia and Turkey during the sixteenth century. On this volume, the marbling features a simple feather pattern created with a comb and rake, resulting in a random dispersal of colors. The paper is applied continuously on the inner covers to conceal the turn-ins of the leather. The bindery’s stamped mark reflects both pride in craftsmanship and a reputation for producing fine bindings.

During the twentieth century, bookbindings increasingly gained recognition as works of art in their own right, and binder signatures and marks became more prevalent. The spine of this volume features raised bands, the book’s title, and a series of gold-tooled motifs, including two linked hearts and a rose—symbolic references to the book’s romantic content. Beginning in nineteenth-century England, there was a notable rise in bindings that aesthetically referenced the text they enclosed, exemplifying the integration of design and literary content.

Studying this specific volume reveals the careful interplay between craftsmanship, materials, and design in twentieth-century bookbinding. The combination of quarter red morocco and marbled paper demonstrates how binders balanced durability with decorative appeal, while the gold tooling and symbolic motifs show a conscious effort to reflect the content of the work. The stamped mark of Sangorski and Sutcliffe highlights the growing recognition of bookbinding as an art form, where individual binders asserted both skill and aesthetic judgment. By examining the materials, techniques, and design choices in this book, one gains insight into the broader evolution of modern bindings and the ways in which artistry and functionality are intertwined.

14th-century German manuscript, Buch de Natur, attributed to Konrad von Megenberg (German, 1309–1374).

Looking at these three works—the 14th century Buch de Natur, the 1768 Traité des Arbres fruitiers, and the 1950 A Little Treasury of Love Poems—reveals the evolution of bookbindings across time and place. Each reflects its era, location, and the traditions that shaped it, balancing practical needs with artistic choices.

Exploring the Oak Spring Garden Library’s collection in this way has deepened my appreciation for its richness and diversity. From the functional severity of medieval style manuscripts to the refined style of eighteenth century bindings and the modern artistry of twentieth century London, these books show how craftsmanship, design, and culture come together.

Not only do these bindings serve as art in and of themselves, they serve an important purpose in protecting the knowledge within. I look forward to continuing to study these bindings as lasting evidence of human creativity and skill, seeing in each one not just a cover but a story, an art form, and a testament to the makers who brought it to life.

Every Rare Book School course I have taken has offered wonderful perspectives and opportunities to meet like minded individuals who share a drive to learn more about and preserve rare books. I hope to attend more RBS courses in the future, and continue learning about these important gems of human knowledge and creativity.

Written by: Salem Twiggs, Oak Spring Garden Library Associate

Images by: Salem Twiggs and Tiffany West