Connection or Coincidence? Paris, Edinburgh, Kathmandu

Claire Banks

Figure 1

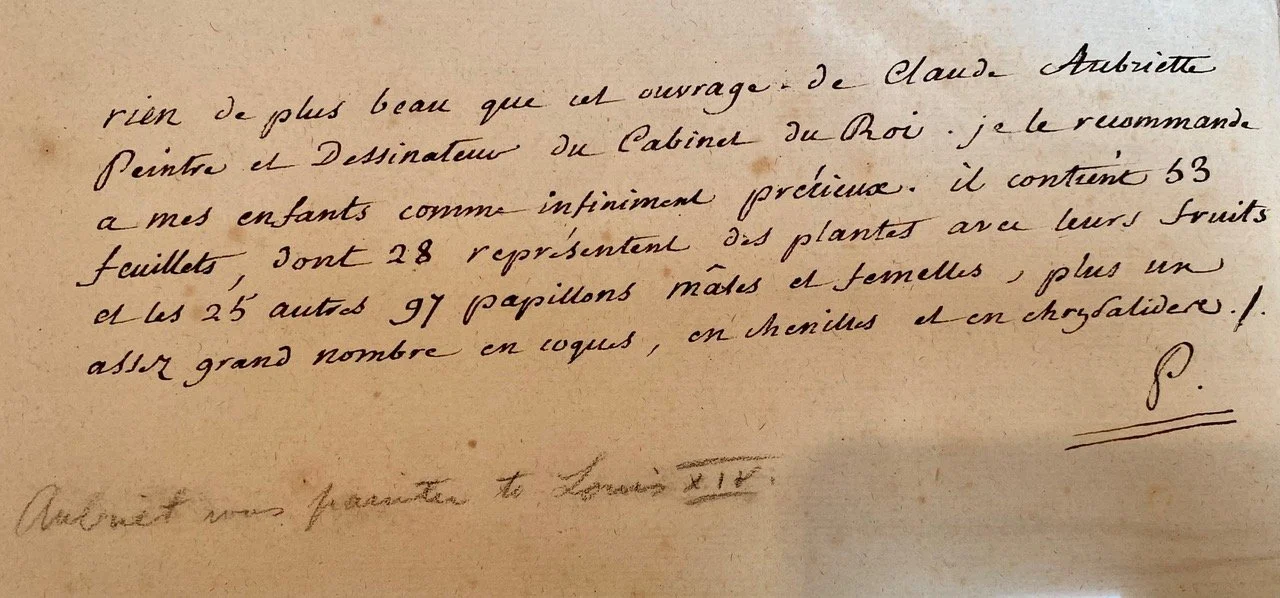

Catalogue No. 00002826 of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation Library lies on the cushion support on the desk in front of me. The leather binding of this volume is a beautiful deep crimson, and the spine is tooled in gold (fig. 1). When the cover is lifted, you are met with richly marbled endpapers in shades of blue-grey, green-grey, purple-red and ochre; the left side bears Bunny Mellon’s unique bookplate. Turn the marbled page over, and on the top of the left side is an ink inscription. Written in French in a 19th-century hand, it reads:

rien de plus beau que cet ouvrage - de Claude Aubriette Peintre et Dessinateur du Cabinet du Roi je te recommande a mes enfants comme infiniment précieux. il conteine 53 feuillets dont 28 représentent des plantes avec leurs fruits et les 25 autres 97 papillons máles et femelles, plus un assez grand nombre, en coques en chenilles et en chrysalides.

(I recommend to you my children this work by Claude Aubriette Painter and Draftsman of the Cabinet du Roi; infinitely precious, there is nothing more beautiful. It contains 53 sheets, of which 28 represent plants and their fruits, and on the other 25 are 97 butterflies, male and female, and in addition quite a large number of caterpillars and chrysalises.)

Figure 2

A simple P is the enigmatic signature. Below the inscription, the words ‘Aubriet was painter to Louis XIV’ are written in black chalk (fig. 2). Added at different moments during the three centuries of the volume’s existence, these notes add to my sense of anticipation. This is a rare privilege.

Claude Aubriet (1665 – 1742) was one of the foremost European artists of natural history subjects in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. His official appointment to the French court began in 1707, continuing until 1735, when he was forced by ill health to retire. As Painter and Draftsman to the Cabinet du Roi, he worked with many famous French naturalists, including Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656 – 1708) and Bernard de Jussieu (1699 – 1727). He was commissioned to produce twenty-four natural history miniatures per year. In this context, miniature painting refers to a particular technique of using water-based paint, often opaque and more like gouache rather than the watercolour we know today. Natural history subjects at the time were usually painted life-size; these miniatures should not be confused with the genre of tiny portraits often painted on ivory. Dated to c.1725, this is a volume of works made at the height of Aubriet’s career.

Figure 3

Inside are the most beautiful images. I agree with ‘P’. These are truly ‘infinitely precious’ works. The butterflies are stunning; however, as a botanical illustrator, I am most attracted by the botanical paintings. Although these works capture as much detail as herbarium specimens, their visual effect could not be more of a contrast. Bound into this volume, minimising exposure to light, the colours of the paints are still fresh and vibrant. A new subject is presented on each sheet, bordered in rich gold, and the majority are painted on vellum. Each plant, whether large or small, fits within the same dimensions, all cleverly composed to display part of the plant’s habit along with the flowers and fruits. The gold of the borders was applied so thickly that it is cracked where the vellum has buckled over time. Designed to define the pictorial space, the plants sometimes escape their confines, as in nature. They almost seem to be growing within the pages: leaves extend beyond the gilt edge, and occasionally a fruit, such as the Melongena from South America, sits in front of the frame, entering our time and space.

Figure 4

The painting of Santolina, a Mediterranean native, perfectly captures the blue-green of the deeply cut foliage, contrasting with the strong golden yellow, button-like, composite inflorescences (fig. 3). A single, life-size whole flower is at the bottom right of the habit section. This strongly reminds me of an image I am researching for my PhD. No. 401D/1/32 [2-21] Liparis petiolata (D.Don) in the Linnean Society of London shows a full-coloured plant, roots to flowering tip, painted in the middle of a sheet of wove paper. A single, life-size whole flower is recorded to the left of the inflorescence (fig. 4).

Figure 5

When the page turns to Aubriet’s Acorus verus, I am astonished to be reminded again of another image I am researching, also held in the Linnean Society of London (fig. 5). The composition layout is very similar in how the strappy leaves are arranged and cut off at the top by the frame edge. No. 410/1/19 [2-9], Campylandra aurantica Baker has a bold composition, in full colour and shows a plant which grows larger than the paper size (fig. 6). To keep the plant at life-size, the long strappy leaves emerging from the root are cut off at half-length along the top of the page. The full length of the leaves is indicated with the inclusion of the top half of a leaf on the left side. But the botanical drawings I am researching were made decades later, in South Asia, by an Indian artist commissioned by a Scottish surgeon naturalist. Surely any similarity to these images, produced in Paris for the King's private collection, is purely coincidental?

Figure 6

The drawings of Liparis petiolata and Campylandra aurantica were made in Nepal between 1802 and 1803 and are part of the Buchanan-Hamilton Collection held by the Linnean Society of London. Dr Francis Buchanan-Hamilton commissioned them from an unknown Indian artist during a diplomatic embassy mission to Nepal by the British East India Company (EIC). Buchanan-Hamilton served in the Bengal Medical Service of the EIC from 1794 until 1815 and was included in the embassy as a doctor. Trained in medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Buchanan-Hamilton studied botany at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE). In the 1780s, botany was a core subject of the medical curriculum: Buchanan-Hamilton continued an active professional interest in natural history throughout his EIC career.

The EIC valued Buchanan-Hamilton’s talents as a naturalist, and he was twice commissioned to undertake official survey work for the company. However, natural history was a passion he often pursued independently. This was the case with his botanical survey of the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal. In addition to his medical duties, Buchanan-Hamilton collected and described hundreds of plant species. Of the 1100 species he came across, he estimated that 800 were new to European science. The 122 plants he asked his artist to record included orchids and gingers, which would not make good, dried specimens. Another reason for commissioning the illustrations was his dream of publishing a Flora of Nepal.

Had Buchanan-Hamilton published his Flora of Nepal, it may have been one of the earliest works arranged by a natural classification system. Antoine Laurent de Jussieu’s (1748 – 1836) Species Plantarum was published in 1789. It outlines a natural system of classification in which multiple plant characters are considered in respect of their similarities and differences. Although the Latin binomial nomenclature system, first published in Systema Naturae by Carl Linnaeus (1707 – 1778) in 1735, is still used today, his artificial sexual system of botanical classification, which concentrated on floral characters alone, was superseded by the natural system. At the time of Jussieu’s publication, Buchanan-Hamilton was working as a ship’s doctor, not best placed to keep up with the latest scientific publications. All his other natural history work is based on the Linnean system: how could he adopt this brand-new method barely ten years after its publication?

Buchanan-Hamilton had pre-existing knowledge of the natural system as taught by John Hope (1725 – 1786), Regius Keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden of Edinburgh from 1761 – 1786. Hope is acclaimed for his early adoption of the Linnean classification system, but he studied botany, part of his medical training, in Paris with Bernard de Jussieu (1699 – 1777) in the 1750s. Bernard de Jussieu was working on a natural system at the time, but he did not publish it. His nephew did; Antoine Laurent de Jussieu’s Species Plantarum was developed from his uncle’s unpublished work. Bernard de Jussieu started working at the Jardin royal des plantes médicinales in 1722 and would have known and worked with Claude Aubriet when volume No. 00002826 was made. Did John Hope see works by Aubriet when he studied in Paris?

Of course, Hope and Buchanan-Hamilton would most likely have known Tournefort’s influential Eléments de botanique, ou Méthode pour reconnaître les Plantes published in 1700 and 1719, for which Aubriet was the principal artist. However, an intriguing detail, shared by the works in the Aubriet album and the drawings made for Buchanan-Hamilton in Nepal, is the lack of floral dissections. While floral dissections were illustrated before 1735, after the publication of Systema Naturae, they became essential information, especially when using the Linnean classification system. The Aubriet works were made before 1735, and perhaps there simply was not enough time when working in the field in Nepal for the artist to include such details. But, given Buchanan-Hamilton’s use of the natural system in Nepal, it is tempting to wonder if the genealogy of ideas, from Bernard de Jussieu, through John Hope, to Francis Buchanan-Hamilton, may be reflected by similarities in these illustrations, despite being made far apart in time and geographical location.